What can we expect from a population decline in advanced economies?

Effects and beneficiaries of population reduction

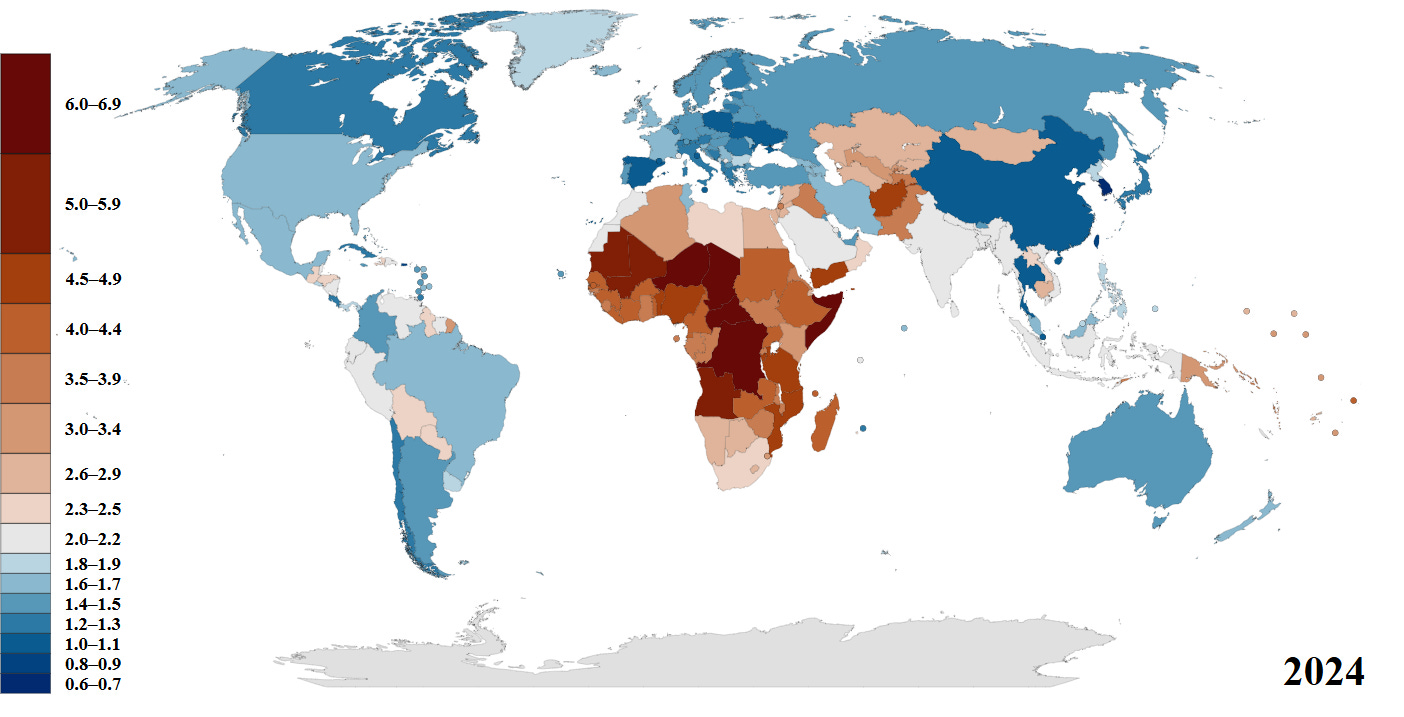

The Covid event and its fallout coincided with a good 0.2% drop from an otherwise relatively stable global population growth level, and the decline seems to be progressive.

Yes, we know that correlation doesn’t equal causation, but as we’ve previously discussed on these pages, it’s increasingly difficult to bring about major changes in something like the birth rate as we approach the more extreme values. It will take exponentially more powerful causes to bring down an already very low birth rate, or to further increase an already extremely high one, so going from about 1,1 to 0,85% over 2-3 years is quite remarkable, whereas a similar reduction from levels of e.g. 3% would be much less significant.

But whatever the actual causes behind this progressive drop in fertility, I thought we could make a few simple observations around what kind of direct and indirect effects this sort of development could bring about for a late-stage industrial society such as ours. What should we expect from birth rates dropping and an historically extremely old population in relation to a geopolitical, cultural, economic and technological situation such as the one we now find ourselves in?

Difficult questions, to be sure, and any answers will tend to be cursory and superficial. But even so, there are a few observations based in more or less immutable factors we can make that are likely to enable decent mid-term predictions.

Economic growth is going to stagnate and drop in line with the population

So let’s assume an enduring population decline throughout most of the advanced economies of the world. This is going to translate to a reduction in terms of goods and services produced, i.e. a drop in economic activity. Even if industrial output could to an extent be kept up through increased automation, the economy needs markets to maintain a demand for whatever is produced, and with a stagnant or shrinking population on the broader scale, over time, both the demand and purchasing power of the market is going to decline through various direct and indirect mechanisms.

Global TFR (total fertility rate) is now just above replacement level, and in the vast majority of advanced economies, it’s significantly below replacement level. This is why low-TFR states like Sweden, Germany and the UK has had to import foreign labor and consumers to replenish the workforce and to maintain the economic growth that is necessary within the framework of capitalist economies.

Without immigration, Sweden’s population today would now likely be lower than even in 1970, at around 7 million as compared to today’s 10,7 million, and economic activity, productive output as well as market demand would reflect this lower number.

A stagnant population in a finite world isn’t necessarily and under all circumstances a bad thing, of course. But while a steady-state economy where labour must not necessarily be maximally exploited for profit could more effectively address imbalances relating to an aging population, the modern capitalist economy not only incentivizes growth, it is structured in such a way that a lack of continued expansion very often means collapse. This is especially because of the myriad ways debt is integrated throughout the economy, and the way that modern financial markets are geared towards maximizing profit in the shortest amount of time possible.

Debt servicing is going to be increasingly difficult, if not impossible

So on that note, if economic growth in general started to come into question for real, then the capacity of borrowers to actually repay loans through future increases in revenue would be equally doubtful. This will cause capital flows to freeze up, inducing defaults across the board in our overleveraged global economy, since the risk of lending would generally be unacceptably high. This would quickly bring economic activity to a relative standstill, and over time force a relocalization of production and consumption. And since the global economy and its resource and capital flows are not only interdependent and integrated to an extreme degree, but also lack redundancies at almost every level (TSMC in Taiwan produces 90% of all the world’s semiconductors as a prominent but far from unique example), a transition towards relocalization would be incredibly disruptive and painful in large parts of the developed world.

A progressive “simplification” of the economy will ensue

But as population decline puts downward pressure on economic activity, the economy will inevitably have to simplify to a certain extent. It will have to trim away some of the expensive complexity that can be profitable in a globalized growth economy but which is no longer viable without cheap or at least accessible credit. Whether or not this can be navigated in the long run remains to be seen, but in the short term, impaired access to global markets and supply chains will force the emergence of simpler and less interconnected solutions, which means that we will have to get by without access to many goods and services that society is accustomed to.

Increased intergroup conflict

This situation also means increasing and quite probably widespread poverty and mass unemployment. People will be forced to fall back on their own limited immediate resources, not least since establishing meaningful local and regional substitute production will be painstakingly difficult. You can’t easily finance it, there will be few reliable supply chains, and the deskilled and/or hyper-specialized population is not going to be a very effective labor force when everything has to be done on an ad-hoc basis.

As this outcome becomes more and more likely, we are going to see serious conflicts proliferate between various groups on many levels, and certainly along ethnic, religious and political lines. Attempts to offset the population decline through immigration has been an integral aspect of European politics for more than 50 years, but even with half a century of integration efforts, the ethnic and cultural landscape is certainly too fractured to hold up very well in the face of genuine, long-term economic decline.

The aspect of intergenerational conflict will also become increasingly important. The demographic pressure on the welfare state due to a shrinking working-age population is already straining public debt, and a growing portion of the income of younger generations is going to be appropriated just to keep things afloat.

Initial pressures to increase immigration from high-TFR regions

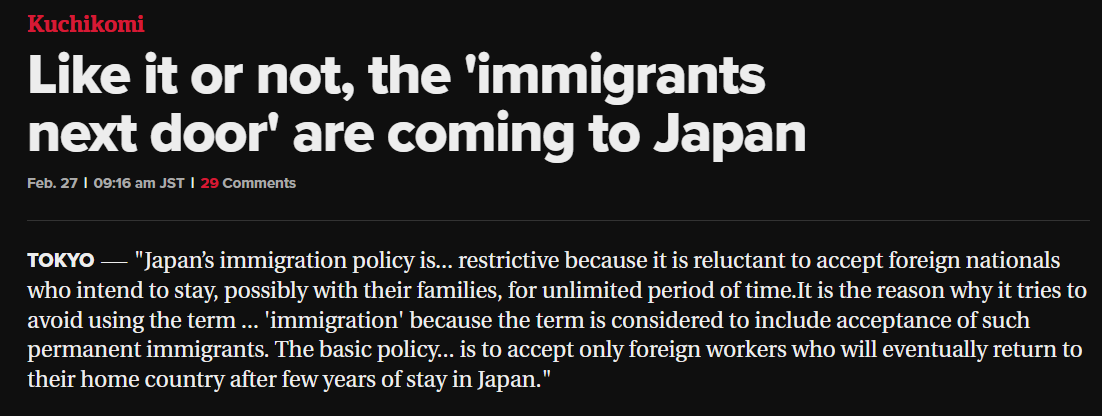

Countries like Japan, with almost no previous immigration to speak of, are going to face unique challenges as the efforts to offset the population decline intensifies in view of the emerging economic realities. Japan is a unique example since the country’s economy was shielded from much of the immediate economic impact from population stagnation and decline due to various factors such as targeted fiscal stimulus and the yen carry trade as well as significant productivity increases strategically geared towards indispensable high-tech exports.

But now, as Japan is coming up against the hard limits of economic activity due to the its super-aged demographic structure and miniscule birth rate (almost a full third of the population is 65 years or older), the country is starting to face serious problems. This is not least in relation to the massive pension crisis currently brewing. So decision-makers are now scrambling to make up the shortfall in the workforce, especially with regard to lower-income and menial jobs, through targeted immigration.

Since Japan doesn’t really have a history of immigration to speak of, this pivot has of course inflamed tensions and bolstered nationalist and radical right factions, such as the newly-formed Sanseitō party which quickly has amassed an impressive support among younger citizens. And in spite of Japan having basically no immigration whatsoever when compared to European states such as Sweden, with almost a full third of inhabitants with a foreign background, these comparatively minor stirrings are already causing quite an upheaval in Japanese politics.

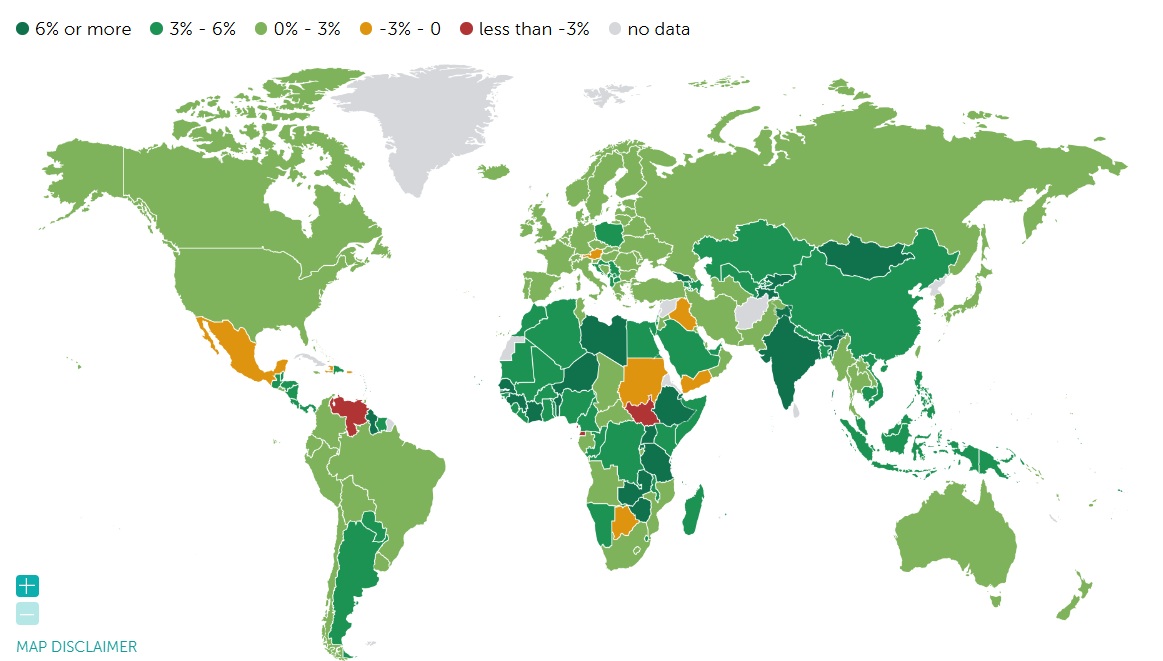

But as economic activity picks up in many of the high-TFR states from which the declining advanced economies are planning on sourcing new workers, emigration from these places might very well become a progressively less attractive prospect.

Many African nations have plenty of room for expanding economic activity resource-wise, and overall have a relatively small population with regard to its available real estate. And if things are picking up back home, maybe leaving your family behind for an uncertain future on the other side of the world is not going to be such an easy sell.

This leeway in terms of local and regional productive capacity also means less vulnerability in relation to a global economic contraction and a stagnant population. “Advanced economies” which are not self-sufficient in terms of locally available resources (such as South Korea or Japan) have little to fall back on in a situation of prolonged contraction and will face much more significant economic and social upheaval.

Rising geopolitical tension

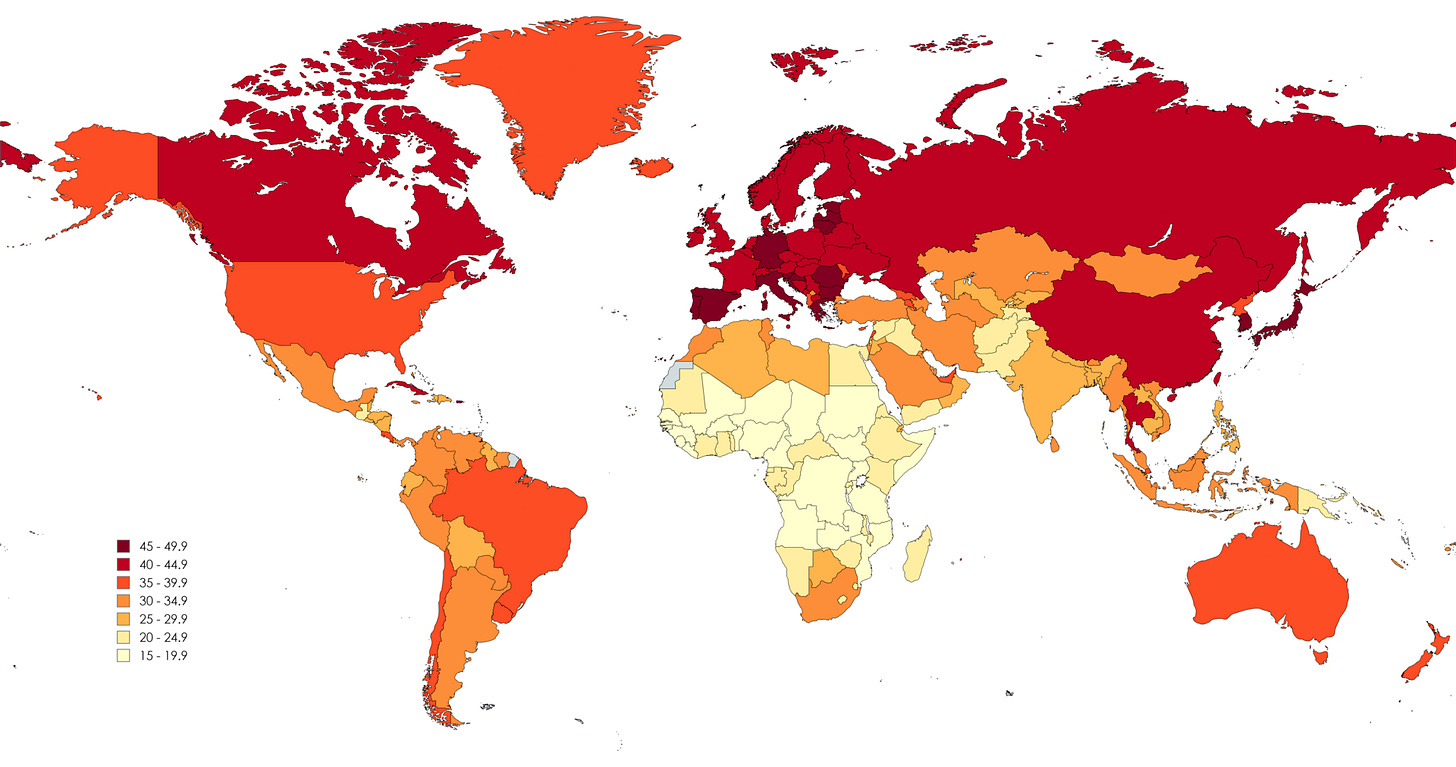

Today, the importance of raw population numbers are not always discussed in relation to geopolitical power projection. It’s offset to some extent by automation and the technological force multipliers available to most of the world’s armed forces, but these aspects are exaggerated in certain respects (recall the disproportionate impact of the rag-tag Houthi forces over the last few years), and effective military power projection over the longer term always necessitates a robust economy in the background. If the populations of the developed world continue to progressively decline, the prospect of real and violent competition with the young and rising powers in Africa and Southeast Asia is certainly going to materialize.

The numbers in this map below are really daunting. The median age in many of the most economically promising and resource-rich regions of Africa is between 15-19 years. In Japan, it’s about 50; in Germany, around 48.

If the people living in these places suddenly decide that they’re no longer interested in continuing the colonial relationship of supplying the “advanced economies” with labour and resources, I don’t see how anyone would be able to stop them.

Legacy notions of human rights will be shelved if and when they conflict with economic necessities

Finally, we can safely assume that the economic and social chaos following on a prolonged economic contraction in the developed world is unlikely to favor established 20th century human rights discourse. Authoritarian politics will follow from both the increased geopolitical tension and the intergroup conflicts emerging within societies. As the survival of one’s own group is under threat, the rights of the out-groups, such as immigrant populations, will be undercut — something which we’re already seeing in the explicit policies of Japan’s ascendant radical right.

In terms of women’s rights, we’re first going to see reinforced pronatalist policies, iuitially through targeted incentives, but as groups like the radical right gains ascendancy, there will be a rollback of anything remotely deemed to impact fertility numbers. Abortion and access to contraception will be restricted. The care burden of the aging population is also certain to disproportionately fall on women, especially as a relocalization of production will increase the scope of more physically demanding types of labor.

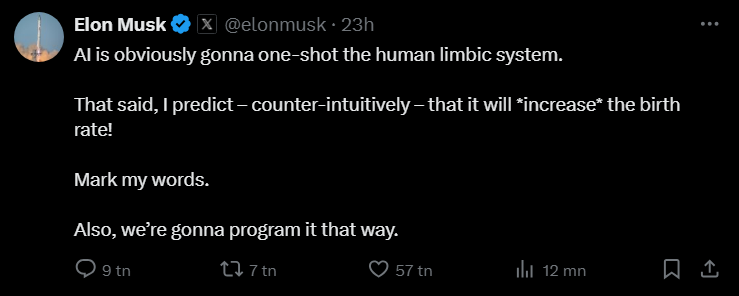

But don’t worry, Musk is going program us all to breed using his AI.

I like this honest tin god tech despot vibe.

I don’t know what these delusional nepo baby social engineers are on about, but let’s just say that their magic plagiarizing chatbots aren’t obviously stimulating meatspace interaction. These examples of the contrast between Musk’s prominence and relatively limited intelligence are always a source of amusement.

Final notes

The overall impact of a population decline in the current societal context is going to favor authoritarian political and institutional outcomes, especially as a kind of innate response to the inevitable austerity and painful transitions that would ensue.

But this also provides ample opportunity, and means that established institutions devoted to surveillance and social control could potentially leverage the situation towards further increasing their power and influence, at least as long as a proper economic collapse could be averted.

I suspect that the desire to both avert a deeper and more extensive strife (as per the collapse of basically every earlier complex civilization) due to growth-mediated over-extension, while also consolidating power in the hands of a select few elite organizations could be a very attractive set of incentives to try bringing about a soft rollback of what is commonly believed to be unsustainable population numbers (and levels of resource consumption), especially in the high-maintenance advanced economies.

In other words, in spite of the likely massive global economic disruption that a progressive population reduction would entail, it would arguably also foster the institutional and social development of far-reaching technological control structures and social engineering efforts that certain influential social imaginaries frame as crucial for mankind’s continued trajectory towards a technological utopia.

Deep down, I feel that compound interest is inherently incompatible with a stable or decreasing population level.

Somehow, we need to get rid of the financial rent seekers peacefully, or pretend this is not a root problem and let things stay as they are until they get ugly and violent.

Cool, ' now that's something everyone can enjoy'. Stark stuff indeed Johan, so basically from here on in it's going to be the Mother of all kicking the can down the road until the horsemen of the apocalypse ride over the horizon.