Japan's strange fertility anomaly of 1966

On the alleged massive effect of the astrological "Fire Horse curse"

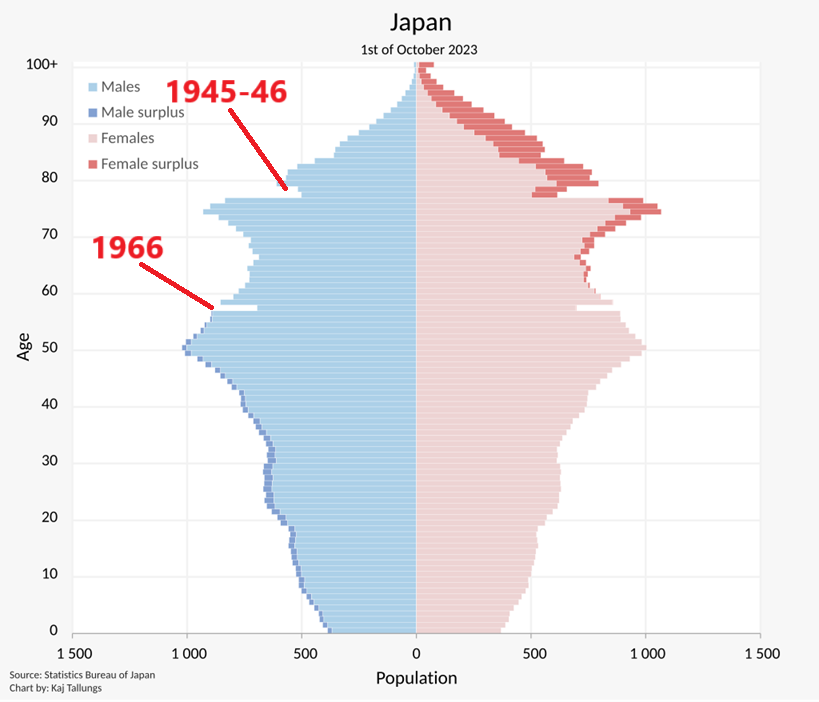

The other day I was casually reading up on the age distribution of Japan’s population, and I saw this really wild gap in the statistics, seemingly emerging from out of nowhere in the mid-1960s.

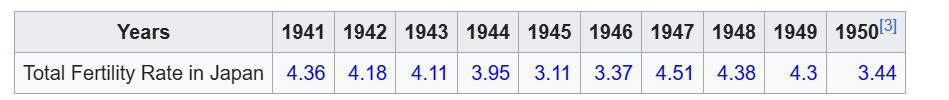

In 1966, the TFR shows a huge and unprecedented drop, which also occurs in the middle of a significant up-trend. It bucks the trend with impressive force, and is then gone the following year, with the trend still in place — implying that whatever factors caused the trend must have been effectively displaced by the explanation of the TFR drop in 1966. I.e. the causes of the latter must have been pretty strong.

You almost don’t believe your own eyes. That’s quite some notch, right?

As a comparison, you can also see the significant fertility decline after the Second World War and the subsequent occupation and violent restructuring of Japanese society. Coupled with what amounted to a massive collective existential crisis manifest in the submission of the divine imperial state that everyone on some level identified with, a decline in live births of some magnitude was to be expected.

And you can clearly see this in the data. There’s a significant drop-off in fertility during 1945 and 1946 in comparison to the previous trend, down from 3.95 in 1944 to 3.11 in 1945.

But this comparison makes the 1966 drop-off all the more astonishing. The 1944 decline had a number of strong proximate causes and is indeed significant enough, yet in 1966, we get close to a 25% reduction in the TFR, in the middle of an up-trend, and from the already much lower level of about 2.1 down to 1.6.

The loss of expected births is almost as many as the number of children who were actually born in 2024, and the drop is from already historically low levels.

This is really curious, to say the least.

Major moves beyond the extreme ends of values like the TFR, such as going from very high levels of fertility to an additional 20% increase, or from very low levels to further drops in the double digits, take unusually powerful causes, since we’re dealing with things in the real world and not something like stock or crypto prices. So if you have a biological entity like a human being, and you want to move its behaviour or its operations further and further away from its averages or its norms, you will have to push proportionately harder, or there will have to be uniquely potent causes in play.

This would not be necessary if the deviations are closer to the normal spectrum of behaviour or operations, more in line with the biological, mental and social equilibrium of the species.

It’s similar to how you shouldn’t expect to see persistently elevated excess deaths after a disease outbreak in a population has killed off most of the weak and vulnerable individuals — it would take additional significant or causes to explain such a persistent elevation.

Even so, the established mainstream explanation for this strange anomaly is that it’s somehow due to the impact of a “folk superstition” that’s supposedly unique to Japan (since you don’t see anything equivalent anywhere else in East Asia):

I only find two significant published articles that address the phenomenon in detail (the other one is here), and both of them seem to just accept the superstition hypothesis without really interrogating it further, for instance through actually verifying that there are plausibly representative examples of people putting off having kids in 1966 exclusively for this reason.

Although there’s no sense in discounting the Fire Horse year as a significant contributing factor, it seems to me that it’s insufficient considered as the only, or even most significant cause of something like this.

It’s a really powerful drop, from already very low levels, and in the middle of an up-trend.

2.1 - 1.6 over one single year:

So in terms of addressing such suspicions, how do we go about interrogating this mainstream hypothesis with the little data we can get on the phenomenon?

Well, what we can do, which is not that much, is still pretty straightforward.

A. We can assess the significance of the observed change in the TFR, as I’ve already discussed above. It’s a really powerful drop, in the middle of an up-trend, and from already quite low levels. And it’s more severe than other comparative changes in the TFR, such as indicated by the data of -45 and -46. So we know it’s something that would take a really powerful cause.

B. We can ask ourselves how powerful the proposed astrological “folk belief” cause should be, and this is admittedly quite iffy since we’re dealing with a whole host of unknown variables. There’s very little to go on in terms of getting a decent outline of what sort of social phenomenon we’re dealing with here, and how much of an impact it reasonably should have had in 1966.

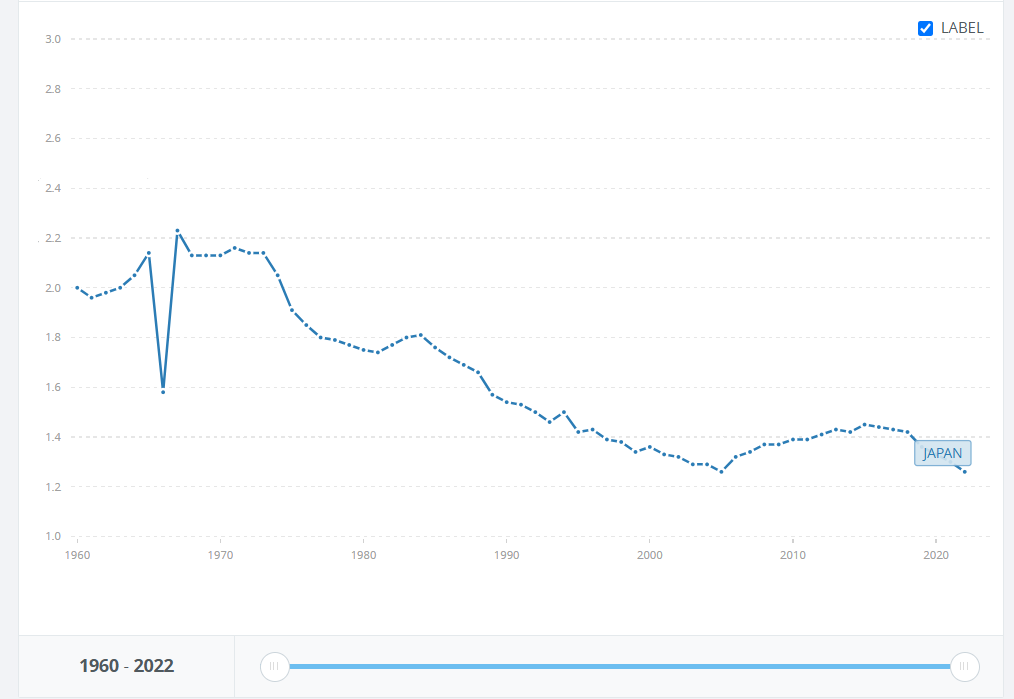

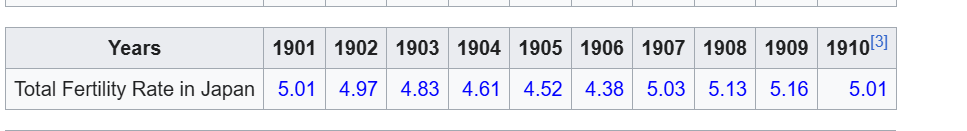

But since it comes around every 60 years, we can at least start out by looking at the data from 1906.

And as you can see below, they do show a reduction in the TFR, but it’s moderate. In relative terms, the reduction is about 3%, and in absolute terms, we lose 0.14 as opposed to 0.5 in 1966, and also from a much higher total fertility rate (4.52 - 4.38).

Now, I assume that these numbers are not as reliable as the 1966 data, but even so, it doesn’t seem that the Fire Horse belief had as much of an impact in 1906.

Of course, this can be for any number of reasons. Maybe the belief wasn’t as established back then, or maybe it was displaced or suppressed by other trends in the worldview or the dominant religious discourses.

But there were significant trends and social processes present in post-war 1966 that we should expect to counter the impact of a “folk superstition” based in astrology. We had secularization, modernization, and a general imposition of Western culture. There was nascent feminism, and a strong and influential wave of Social Democracy and various strands of Progressivism.

All of these are factors which verifiably suppressed traditional belief-systems and folklore, and which would certainly have seen a tension in relation to a superstition that especially targeted female children.

You’d expect the effects of these belief structues to have weakened — or at the very least to not be as much stronger as they were in comparison to 1906, but that doesn’t square with the Fire Horse hypothesis.

There’s also the issue that there’s really nothing equivalent anywhere else in East Asia, and since you’d assume that the “superstition” would at least be present in Japan’s former colonies and protectorates like Taiwan, it’s strange that it’s entirely endemic to Japan only.

C. So what alternative explanations do we have for the TFR drop-off, that perhaps may also synergize with the superstition hypothesis?

As one of the two articles above detail, there were an increase in abortions, but that alone would only explain about 5% of the total missing births. Even so, an increase in abortions, however small, may mirror a general determination not to have children in 1966 and indicate causal factors we are not aware of.

Chemical contraceptives is probably the first thing that pops up in a Westerner’s mind, but they actually weren’t legal in Japan until 1999, and not in widespread use thirty years earlier.

So were there environmental factors that could have suppressed fertility, directly or indirectly (such as making people wary of birth defects)?

I have no real information on this. Apart from Japan’s first nuclear reactor beginning operations in July 1966 (which could be a factor), there’s little I can find online.

When I raised the topic with some colleagues, some of them mentioned that there was indeed a number of environmental disasters occurring in Japan in the 60s and 70s, yet which are almost unknown today since the information was suppressed as much as possible. “Minamata disease” is a more well-known consequence of this more or less hidden backlog of environmental pollution, but the issues weren’t widely acknowledged until decades after the first reports surfaced.

The increasing awareness of these issues in the mid 1960s, coupled with the astrological convergence as well as the ominous launch of Japanese nuclear power (considering the nation’s recent history) may perhaps cumulatively go some way towards explaining the incredible drop-off in the TFR of 1966.

Or maybe there were also significant environmental factors, such as industrial accidents or pollution events, that directly contributed to a loss of fertility and which have been entirely hidden from view.

We don’t know.

The point is that the entire mainstream simply accepts and reproduces an explanation which is obviously unsatisfying if one just scratches the surface a little bit.

And I have to reiterate, this phenomenon was so significant, that in comparison, if there are no children born at all in Japan in 2025, this would still be a less-significant reduction in the number of expected births in comparison to 1966 if we adjust it in relation to the total population.

Would you accept a “folk superstition” as explanation for such a situation in 2025?

Maybe. If a narrative is properly seeded by the news agencies or the dominant institutions, we will tend to accept it without much further questioning:

And so perhaps — if I may go out on a limb here — perhaps there are also similar critical questions we could pose in relation to the uncannily similar mainstream explanations of the unprecedented drops in birth rates we’re now seeing all across industrialized nations in the post-covid landscape?

Does that mean that 2026 is going to be another year in low births in Japan?