The fault lines between East and West in the cold war were almost exactly those that divide Orthodoxy from Western Christianity. Which of course are more or less the same ones that used to separate the Western Roman Empire from Byzantium.

And when Charles “Martel”, the hammer of the Franks, managed to rout the forces of al-Ghafiqi (Abd-al Rahman) at the Battle of Tours in 732, the demarcation between Islam and the West was definitively cemented as well. One can just imagine how history would otherwise have proceeded had Martel’s phalanx broken at the onslaught of the Umayyad cavalry. In the end, it probably came down to the experience and determination of just a handful of men that had been campaigning with their commander all across Europe for more than fifteen years. The old guys who’d seen just about too much, but at least knew how to plant a spear and stand behind it, come what may.

Martel’s victory consolidates the power and identity of the Franks as a people, which in turn paves the way for the Carolingian and Holy Roman empires, sprouted from the galvanizing animosity towards the Muslim Other. At about the same time as the Battle of Tours, Venerable Bede of Jarrow finalizes his great work of more or less single-handedly fashioning the English ethnicity around a similar theme — the conquest of the promised land by a chosen people. A pressing consciousness of the fated appearance of the Saracen features prominently in the background:

In the year of our Lord 729, two comets appeared about the sun, to the great terror of the beholders. One of them went before the sun in the morning at his rising, the other followed him when he set in the evening, as it were presaging dire disaster to both east and west; or without doubt one was the forerunner of the day, and the other of the night, to signify that mortals were threatened with calamities at both times. They carried their flaming brands towards the north, as it were ready to kindle a conflagration.

They appeared in January, and continued nearly a fortnight. At which time a grievous blight fell upon Gaul, in that it was laid waste by the Saracens with cruel bloodshed; but not long after in that country they received the due reward of their Unbelief.

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731).

But whether one likes it or not, the deep and enduring dividing lines between Islam and the West are mostly of a religious rather than political nature.

This is a statement which needs to be clarified, perhaps. I don’t mean religion in the sense that people’s faith in God somehow reproduces violence and animosity. That one holy thing is something else entirely. Ask Rumi, for instance:

With one heart, one worship, one aspiration!

And schism and polytheism and duality disappear,

And Unity abide in the Real Spiritual Being!

When my spirit recognizes thy spirit,

We remember our essential union and origin.Spiritual Couplets.

But when we look at the hard, thorny framing of Islam and Christianity as these star-crossed lovers, it’s evident that there’s a certain antagonism even at the outset. There are core features of these religious traditions that inevitably will generate a strong reaction when you put them together.

“Never could I say that I am to be worshipped”, the Quran reports Jesus as saying. “I do not know what is in Your heart”, Christ the Messiah responds to Allah.

The Quran, of course, according to Islamic ortodoxy, is the single greatest miracle in the history of the universe. The uncreated word of God, as Sunni Islam has it, or the greatest of created things, as Shia Islam argues (since if the Quran is actually uncreated, then how could one avoid a Divine Binary Dyad equivalent to the Holy Trinity?).

And because of these few words above, taken from the surah Al-Ma'idah, and the inevitable reception of this radical challenge that Islam poses for Christianity, there will be no easy reconciliation. No obvious compromise.

The clear and unambiguous message of the Quran cannot be modified.

And while the Christian can readily accommodate the uncreated Divine Trimurti of Hinduism, the Tianming (天命) of Chinese religion, or even the Nirvana as overlapping with the transcendence of his final redemption, how will he deal with this dagger at the heart of the very meaning of his faith?

(Muhammad) did not prove his new sect with any motive, having neither supernatural miracles nor natural reasons, but solely the force of arms, violence, fictions, lies, and carnal license. It remains an impious, blasphemous, vicious cult, an innovention of the devil, and the direct way into the fires of hell. It does not even merit the name of being called a religion.

St. Juan de Ribera (d.1611).

Islam is just too close for comfort. Too similar to the Christian religion for their mutual attempts at distinction to remain very amicable.

There’s never been a simple way forward here, and after fourteen centuries of war between Islam and the West, this conflict has come to define the very identity of both parties. The existential challenge that Islam poses to Christendom from such an early stage, culminating in the Crusades from the late 11th century, played a significant role in shaping the outlook and cultural mindset that in time generated the expansionist and colonial impetus of modern Western civilization.

The Faustian Spirit of the West is in a crucial sense about reclaiming Jerusalem from the Saracens, as much as it’s a reflection of Abraham’s primordial exile-adventure. The colonization of the New World is a kind of secular reenactment of the Mosaic Exodus, a conquest of the Promised Land, and was indeed often explicitly framed in such terms.

It was catalyzed not only by the terrible crises of the late middle ages, which included the Black Death, the Great Famine, and the Little Ice Age — but also in no small part by the very tangible presence of the Fourth Islamic Caliphate that occupied the entirety of the Holy Land throughout most of the Modern Era, encompassing the ancient Christian heartlands of the Mediterranean, and which was within a hair’s breadth of conquering Vienna in 1529, and again in 1683.

A weakened Catholic Church beset by corruption and abuses also opened the door for Protestant Christianity in the 1520s — which in many ways provided the key foundation of Western modernity, capitalism, and the entrenchment of the industrial mode of production. Max Weber was quite correct when he posited that Protestantism gave rise to the spirit of capitalism, but there were more significant causes than the early prosperity theology of the predestinationist Calvinists.

The first population centres that first responded to Luther’s radical new message were those of the Hanseatic League along the Baltic, as well as the Free Imperial Cities of the Holy Roman Empire. These more or less self-governing entities, out of sight of the imperial authority, were key facilitators of trade and of the mass communications technology of the day, i.e. the mechanical mass reproduction of books and printed materials.

And the reason that these polities tended to embrace Protestantism was not only related to the latter’s efforts to undermine the authority of the Catholic Church, and how this would further expand the power of this incipient bourgeoisie. Another crucial factor was Protestantism’s deregulation of usury, which was opened up for renegotiation even in the early writings of its forerunners such as Calvin.

This deregulation was instrumental in providing the groundwork for the colonial expansion of the European powers from 1500s and onward, since it made private investments in these kinds of ventures much easier and way more profitable. This deregulation of capital markets and of how property could be leveraged also enabled the development of the joint-stock company, the first kind of modern corporation, which both limited risk and liability on part of the owners, and provided a vehicle for profitable moneylending.

So the free cities of the German Imperial State, and the citites of the proto-capitalist confederation known as the Hanseatic League, were among the first to formally adopt Protestant Christianity, not least because this provided a significant business advantage over the longer term. And since the free cities dominated trade and high-technology industrial production, they also provided support for the further mass-production of Protestant literature and propaganda.

The latter’s impact can probably not be overstated. A rapid spread of Bibles, pamphlets and assorted literature throughout the most important trade routes, complete with illustrations emphasizing the preferred theological interpretations, and monopolized by the reformers during the crucial initial years of the movement, must have been completely irresistible.

But what’s always overlooked here, is how what’s arguably the very essence of Protestantism — the sola scriptura, the idea of Holy Scripture as the exclusive and infallible source of guidance for Christian faith and a righteous human life — is actually an accommodation to Islam.

Even during the early Middle Ages, the tenacious remainders of Second Temple Judaism posed something of a difficult contradiction in the view of imperial Christianity, culminating in forced baptisms and expulsions. The radical new message of Christ entailed that the Law was now written on the human heart through the presence of the Holy Spirit, enabling an hitherto unimaginable intimacy between God and the believer.

The principle that Paul had fought for, and which had come to render Christianity irrevocably distinctive from Judaism, was clearer, perhaps, to Jewish converts than to Christians – most of whom had never met with, still less talked to, a Jew. To accept Christ was to accept that God could write his commandments on the heart. Again and again, among those Jews in Carthage whose compulsory baptism had been followed by an authentic conversion, this was the reflection, this the change in assumptions, that they had found the most overwhelming.

‘It is not by means of the Law of Moses that creation has been saved, but because a new and different Law has risen up.’

The death of Christ upon the cross had offered humanity a universal salvation. There was no longer any need for Jews – or for anyone else – to submit to circumcision, or to avoid pork, or to follow detailed rules of sacrifice. The only laws that mattered were those inscribed by God on the conscience of a Christian. ‘Love, and do as you want’.

Holland, T. (2019). Dominion.

The arrival of Islam, however, was something of an entirely different order. Islam, with its novel and bold proclamation of possessing the uncreated word of God, unfiltered and sullied by no human being, while also appropriating the core messianic claims of Jesus and acknowledging key parts of Christianity’s message — even venerating the Holy Virgin — was a threat to Christianity unlike anything else prior.

Islam not only navigated the crucial stumbling blocks that had impeded Christianity’s message from the outset — e.g. the Incarnation, the undesirable bodily resurrection, and the ignominious crucifixion and unthinkable death of God.

Islam also, all at once, through the infallible Quran, provided a fount of easily accessible albeit perhaps shallow existential certainty (akin to that of modern redemptive scientism, more on this in a later piece) that also permeated and solidified the political order — where Christianity relied on the individual believer’s radical intimacy with the Divine itself, and cared little for the world, to which Christ’s disciples did not really belong anyhow.

So in the immediate aftermath of the 1300s, with the Black Death killing up to 60% of the European population, just on the heels of the Great Famine of 1315, putting a decisive halt to the prosperity of the high middle ages, invoked an atmosphere of radical uncertainty where despair and catastrophic death could strike anywhere and at any time. On top of this, the Western Schism between 1378 and 1417, and the Hundred Years’ War ending in the 1450s, signified internal fractures within Catholicism that at least on the face of it served to challenge the institution’s claims of infallibility and divine guidance. Luther’s ire over the indulgence markets was just the final straw.

What Protestantism does in this situation is then to radically reinterpret the role and meaning of Holy Scripture on a Quranic template. Consciously or not, Sola scriptura is basically an Islamic mode of interpretation applied to the Bible, which while in a sense reverting to a pre-Christian understanding of the Law, brings the immediate and tangible benefit of the easily accessible existential certainty that late-medieval Europe so desperately needed. And, in time, an entirely new model of political theology.

Indeed, this is also a clear feature of Luther’s own private life. Certitude was the predominant question, which is crucial to the psychological foundations of the Reformation as well as the emergence of the entire modern Western worldview. It’s the loss of stability and certitude that prompts the abuses, such as the sale of indulgences, that the early reformers criticize, and it’s the need for certitude, in Luther’s own biography, that leads him to emphasize the radical new notion of undeserved salvation through faith alone, and how the believers are actually assured of salvation unless they completely and intentionally reject the faith.

Technically, the Catholic Church never disagreed on the core of these theological principles, and had long since rejected as heresy the idea that salvation could in any way be merited — but this had clearly been obscured by the circumstances and not least the abuses around the indulgences.

And on top of this, Protestantism adds the entirely novel idea of sola scriptura, which more or less appropriates the Islamic notion of holy writ as God’s literal and infallible Word.

What happens then is more or less predictable. The framework of Catholic authority collapses, since the Church and the priesthood are displaced as necessary conduits of religious truth. Everyone can now access the infallible word of God through the magic of the printing press — objectively and absolutely true information about reality that can be translated into any language or set of symbols without loss or remainder. Every man his own bishop (yes, this is also crucial for the later development of the reductionist worldview).

Then, inevitably, you get a power vacuum with regard to political legitimacy that rapidly gets filled by the political power structure itself. Henry VIII becomes the head of the Church of England, and any kind of dissent becomes associated with blasphemy. Sweden’s aristocracy aligns itself with the Reformation to dissolve the Kalmar Union and consolidate its own regional power, and Gustav Vasa soon expropriates the churches, founding the Swedish unitary state with a hereditary monarchy and standing army.

The political-theological innovation of the Divine Right of Kings almost immediately supersedes Catholic authority, which gives rise to the absolute monarchy and the development of the modern Western view of the state, surprisingly very much in line with the basic principles of Islam’s tawhid. God is one, and equally undivided must the response of creation to God be. Church and state cannot be meaningfully separated.

And in spite of their widespread nominal dissolution in the wake of the Enlightenment, this process is really to be comprehended as a continuation along the same trajectory. The secular fount of political legitimacy is rather akin to an appropriation of Divine Right for the bourgeoisie, consolidated in the new ruling class through removing the final remnants of ecclesiastical authority.

The worship of the highest must be undivided, just like rational will of the People.

In the shadow of the Ottoman Empire, the greatest power in the world at the time, the West comes to reflect many of Islam’s principles of political theology. Both in terms of the theological developments around Protestantism, as well as expressed in the more tangible institutional transformations.

And as the West finds itself more and more like its estranged twin brother, the eternal Other, their mutual challenge cannot but intensify.

The Orient becomes, at once, intensely hated and powerfully desired. The literary and poetic imagination of the Enlightenment approaches the Islamic world as the collective shadow of the Western psyche, something violently enticing in its exotic not-quite-familiarity, yet feared and hated precisely to the degree that it reflects those core features of oneself that cannot be reconciled.

Because the West surrendered.

It not only owed a massive debt to Islam for the Aristotelianism of the scholastics and the Renaissance’s recovery of the classics of ancient Greece and Rome. The core parts of Protestantism, the Absolute monarchy, the divine right — even the foundations of the modern project, and the bold swagger of this new basis of political legitimacy identified with the divine rational spark of the citizen, had borrowed core features from tawhid, the essential principle of Islamic political theology.

And for this very reason, nothing could sow doubt and fear into the heart of the Faustian spirit of the West quite like the Muslim Other. What if we’re just like him after all? the shadow constantly reminds us, picking away at our confidence.

What if our empire of reason has but all the substance of the blind faith of the backwater Saracen in the Book of his Prophet?

What will we do if an Islamist regime, which grows dewy-eyed at the mere mention of paradise, ever acquires long-range nuclear weaponry? If history is any guide, we will not be sure about where the offending warheads are or what their state of readiness is, and so we will be unable to rely on targeted, conventional weapons to destroy them.

In such a situation, the only thing likely to ensure our survival may be a nuclear first strike of our own.

(Sam Harris).

So we secretly rejoice in the violence.

It’s not only the open resentment of a radical right that sees in the Palestinian genocide a kind of rightful vengeance over Islamic mass immigration. It’s in the smugness of all of these good Christians who blame the victim, who condescendingly remark that the Palestinians perhaps shouldn’t have supported Hamas (if they wanted to stay alive in their open-air prison).

It’s in the superficial and reductive criticism of a bad-apple Netanyahu regime that obscures the deeper colonial roots of the situation, not least the crucial dependence of the economies of the West upon the exploitation of Middle Eastern energy sources.

And it’s in virtue-signalling lamentations that capitalize on the atrocities to score social media points in the attention economy.

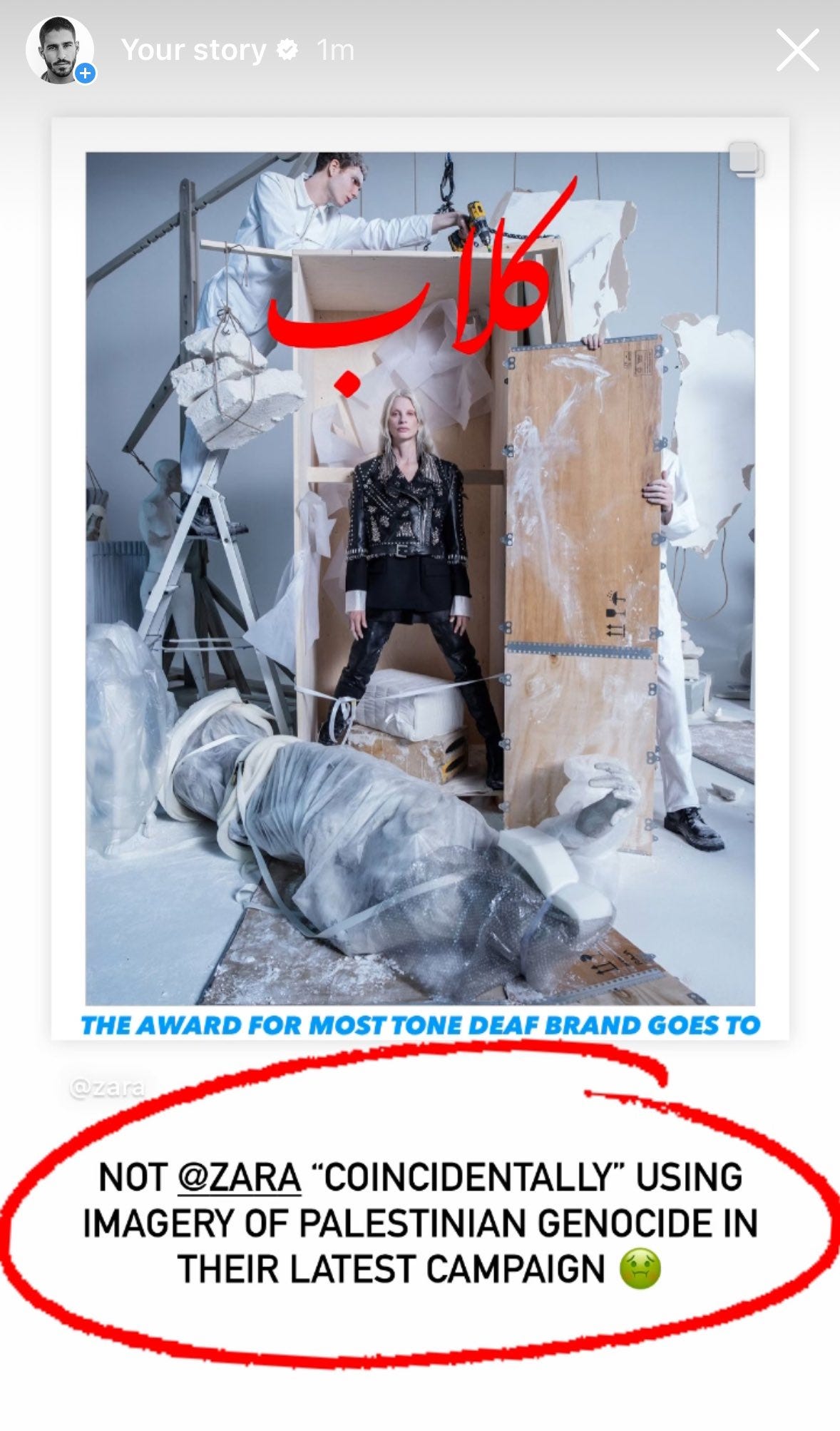

Genocide chiq. Like a one-up of the Zoolander joke about the “derelicte” campaign.

One of the earliest modern literary depictions of the vampire is found in Goethe’s “Die Braut von Corinth”.

Goethe, always preoccupied with the Orient, also approached this supernatural motif as representing a kind of transcultural otherness, a traumatic hybrid that cannot be reconciled with one’s own identity, but which must be overcome or simply endured.

The vampire in the subsequent Western interpretation is always a sort of liminal being, an uncanny bridging of self and non-self. In its early literary context, the vampire is clearly an expression of the colonial preoccupation with its own Jungian shadow projected onto the subjugated Other, rooted in a mutual trauma (and mutual, eroticized animosity) which the vampire, to exist, must both give and receive.

… nor does it work the anti-Christian argument originally underlying the vampire discourse in ancient Greece, where the vampire serves as a discriminatory term intended to mock and disavow the Christian belief in afterlife. While Ossenfelder’s poem clearly reiterates such mockery, by directly relating the girl’s and her mother’s religious ideas to the belief in vampires, Goethe re-verses its very logic: his vampire is at once the ironic product of a Christian exorcism of pagan sensuality and a highly eroticized, and exotic, figure. The eroticization of the vampire (with which Ossenfelder had already played) doesn’t so much confront its counterworld, be it Christian or oriental, but rather emerges from the encounter with it.

Endres, J. (2020). “Vampires and the Orient in Goethes ‘Die Braut von Corinth’”.

Goethe places the vampire in Corinth, in the Ottoman Empire — Bram Stoker’s Dracula is likewise situated on the frayed outskirts of the Orient, but its meaning is here more clearly an expression of the secret embrace of the shadow self.

The myth of the vampire is many different things, but it’s no coincidence that the roots of its modern framing connect it to Vlad the Impaler, folk hero of the Hungarians, who slaughtered the Ottomans in droves, and who enduringly represents the seductive shadow. An equally feared, equally desired projection of our own essential being.

The fratricide, the brother-killer, who secretly rejoices over the genocide in Gaza.

Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?”

He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?”

(Gen. 4:9)

If you have a belief system that rewards power, you'll have stupid civilizations.

The black death probably killed so many because they were malnourished.

But today we still talk about this ghost or demon called viruses.

No different than the past superstitious people and they still go along with imperialism and economic subjugation.

Gaza will be the graveyard of ideals and universal belief of a just world. True civilization will die under the rubble Gaza unless we collaborate and stop this brutality. We will enter a brutal dark ages of Gaza disappears.

And a three day rotting of body in a cave and then resurrection is a hell of a weak fire side tale from which to build a crusades.