There’s inevitably someting magical absout the solstice. The midwinter one as well as the June occasion.

I don’t quite know why this has always been such a strong sentiment of mine — I was just about to write that I didn’t grow up in a culture or society preoccupied with these astronomical events, but thinking more closely I definitely did.

Frost permeating the aging wood of century-old buildings, the sky a frigid purple, your face numb in the faint glow of midwinter’s brief and fading sunlight. In northern Sweden, both of the solstices are powerful, tangible realities. They are the the turning-points of the indubitable seasonal rhythm by which everything moves, even this ostensibly modern life.

Impenetrable, oppressive darkness in late December, a womb of hibernation and familial intimacy, and in summer, an endless day marked by leisure, freedom and unbridled activity. A deathless spark of adventure and outward expansion.

Sweet smell of pine trees, conifer forest, in the hottest first weeks of July — still a million years from the safely suffocating abyss of winter.

And something which I find difficult to express in mere words is just how this violent antipodal interchange also serves to bring depth, meaning and direction to the other, more subtle, seasonal shifts.

The Sami of the north counted eight distinct ones, two sub-divisions each of the conventional seasons, readily apparent to a people living in radical proximity to nature, moving with herds of reindeer, but perhaps less important in the calendar of my farming Norse ancestors.

Even so, spring and autumn up here are powerful transitions in their own right — spring paradoxically both death and rebirth, violently flooding your hibernating torpor with an uncompromising light, forcing your drowsy mind and quieted spirit to deal with the sharp edges of the almost incomprehensibly vast day now suddenly ahead of you.

The homely autumn, on the other hand, invites you to return yet again to the gravelike bosom of the life-giving Earth, smelling of intoxicating wet soil, drawing you towards the tangible and material love of home, hearth and family. Bringing you back down from the almost transcendent brightness of summer’s high.

All of this is irreducible.

Everything I’m describing above are unfathomably complex experiential realities that cannot be exhausted by the finite approximations of language. You can write poems about the cold sunlight of some quiet October morning until the end of time, and the simplest, most cursory human experience of the actual thing will still have depth and meaning of a sort entirely new to you, one that you could never have imagined.

You can’t square the circle because it’s simply impossible to count to infinity.

And this is precisely what’s being negated by the technological drive towards mediatization. By digital isolation and the emergent hyperreality. By “AI” in all its shapes and forms. There’s a mistaken presumption of the limitless viability of reductionism in all of this, that actual reality can be translated, without remainder, into interchangeable abstract information.

That we’re just meat computers encased in bone and flesh, and consciousness nothing but the “firing of neurons”.

But the problem is that any theoretical description is an approximation one step removed from the actual world itself. It’s a one-dimensional reality being used to convey, as far as it’s possible, a three-dimensional one. And you can go pretty far along this path, you can produce some impressive results, but no matter how many angles you add to your increasingly round-ish figure, you will never actually get a circle. The two kinds are incommensurable, so there’s an infinite gap between them.

And when I hear how common it seems to be among the younger generations to engage with systems like chatGPT as a sort of companion, as a real relational agent, it’s this infinite gap that concerns me the most. This progressive substitution of an increasingly plausible pseudo-agency for the genuine human subject.

The replacement of the real with a simulacrum that ever more perfectly masks the abyss hidden within.

The Aristotelians emphasize how the mind in a sense becomes the thing known, how the intelligible form of the external world in a certain way also becomes the form of your intellect, so that your consciousness now in part gets constituted by the new knowledge.

Modern psychology observes that the human cognitive apparatus gets shaped and reshaped not only by the information it receives, but also by the specific ways in which it gets accustomed to receiving information. This means that we also internalize the “thinking” that is emulated by our media, whether we’re dealing with long-form prose, oil painting or television commercials.

We’re crucially shaped by the message implicit in the medium as such, as McLuhan put it.

And internalizing the non-thinking abyss of a pseudo-cognitive simulacrum, a digital magic 8-ball, is poison on a scale that we have never dealt with before.

It’s not just on the level of habituating our modes of thinking to the simplistic, disjointed and associative framework of mass media entertainment, that Neil Postman and the television critics of the 80s were concerned about. It’s not merely the digital amnesia that outsourcing cognition to the ever-present search engine entails, or how digital skimming and link-surfing disrupts our ability of sustained and meditative deep reading necessary for the meaningful interpretation of complex realities that Nicholas Carr prophesied about in 2008.

Internalizing the AI, and its emulated non-cognition is something utterly alien to the mind as such, like trying to nourish a human body with engine lubricant. We’re not dealing with the mere equivalent of junk food anymore, but with something inherently toxic.

Children “raised by wolves”, who in some way or another grow up without meaningful human interaction become permanently cognitively disabled. It’s akin to how if you’d blindfolded a five-year old for a decade, their visual capabilities will have atrophied and can never recover.

Now, what happens if an entire society not only becomes accustomed to a state of digital isolation, a hypermediated information flow and a lack of genuine human contact — but if its future generations are raised on interaction with a ubiquitous pseudo-relational agent? A para-social entity that exchanges meaningful interaction and independent reflection for something radically non-rational, something seemingly intelligently social that’s ultimately just a hollow simulacrum?

Well, then the center doesn’t hold. Then reality itself begins to crumble — at least as expressed through a social consensus built on the reflective experiences of human beings.

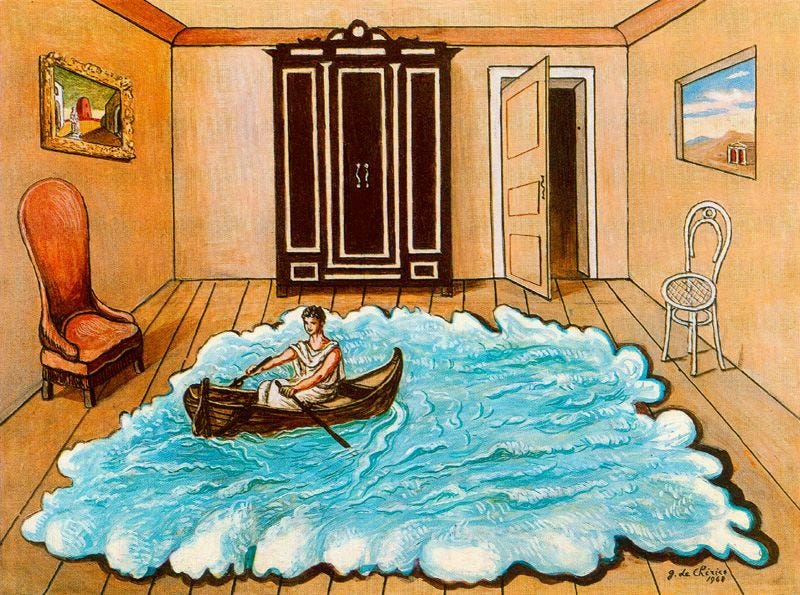

Slipstream is an experimental genre of literature that attempts to transcend the traditional structures of narrative. "[A] kind of writing which simply makes you feel very strange; the way that living in the twentieth century makes you feel, if you are a person of a certain sensibility."

The genre homes in on the uncanny as such, and magnifies it by reproducing its character and effects through a narrative framework that’s disturbing and alien. The uncanny, of course, is often considered to be a sense of unsettling strangeness proportional to the contrast between how familiar and normal something is, and how markedly alien its other attributes.

The distinction between the almost perfect AI simulacrum and the non-rational abyss hidden deep within being a case in point.

Slipstream as a genre is unique precisely because it goes toe-to-toe with the unhuman face buried deep beneath the glittering facades of late digitalization and end-stage capitalism. And in this sense, it also exemplifies a struggle to keep on thinking, feeling and searching for meaning in a society that progessively erodes our basic abilities to do so. On every front.

It’s an attempt to wake up, in spite of the suffocating weight of the nightmare. To furnish something rational out of the patently insane. To once again recognize what is human, if only through unblinkingly fixating on the radically uncanny and its irreducible difference.

For while you can kill or enslave a person — it doesn’t matter what Orwell says — there’s no way you can finally transmute the gold in our souls back down to the dirt from which we were raised up. No matter how arcane or profoundly weird your alchemy may be.

There’s always going to be something of the magic of the solstice left in us, some irrepressible rhythm of the real always at home in the darkest depths of our secret being.

The Doctors have a big debate. It lasts for several hours, but in the end, the pragmatists win out. They will not interfere. They must let things run their course.

They end with the same question they began with. What is love?

It’s quick as the strike of a match to flame. One minute you are a dying body, alone in all the world, and the next you are crouched in a small windowless room beside a boy whose blue eyes make you tremble, whose breathing, somehow, involves your own. Of course it isn’t love.

How could it be, so soon? But the possibility exists. He passes the cigarette to you and you hesitate but he says, Whatsa matter? Afraid you’re going to get cancer? You place the cigarette between your lips, you draw breath. You do that. He watches you, his blue eyes clouded with smoke.

What can you say anyway? How can you explain? You sit, waiting, as though this were an ordinary matter, this beautiful thing, this body, breathing. This terrible judgment. This wonderful knowledge. The body breathes.

It breathes and it doesn’t matter what you want, when the body wants to, it breathes.

Rickert, M. (2006). “You have never been here”. In Kelly, J. P., Kessel, J. (eds)., Feeling Very Strange.

Johan, you've once again written something moving, poetic, profound and deeply disturbing. What you say is true here, of course, and its implications and trajectory unfolding before our eyes is essentially the occult capture and destruction of what makes us human. Yet somewhere there is hope as their technocratic project for complete control is unattainable. Our souls, by their very ineffable nature, cannot be reduced to ones and zeroes.

Have you ever been to a place so invested in navel gazing that it’s totally closed to outsiders, all of whom are made entirely invisible? I have and I’ll never know if it’s an effect of northern latitude or toxic media. Once it goes far enough though, as you say, what matters is irrecoverable