The Setagaya family murders and the meaningless expression of power

On Nietzsche, murder, art and the Olympics

Back in 2000, on New Year’s, a family was viciously murdered in Setagaya-ku, a bit West of central Tokyo. It’s one of the most unusual and troublesome killings in Japan’s modern history, not least since it has remained unsolved for almost 25 years, in spite of a very impressive collection of evidence. You have the killer’s blood, DNA, stool (he seems to have eaten a homecooked meal), most of the clothes he wore during the murders, and even plenty of fingerprints.

I’ve read a bit about this case during the past year, and since the site has been preserved as a sort of ghastly monument and memorial, I thought I’d go see it for myself. Walking there on foot to pay my respects seemed appropriate, so I didn’t take the bus or the train.

It was quite a project. 20 kilometres, all in all, like 12,5 miles, in the pretty serious heat. But there’s nothing quite like walking through a country or a city or a landscape in terms of actually getting to know it. Really letting its atmosphere sink in. Having it imprint on you on some deeper level.

The French philosopher Henri Bergson argued that a city, such as Paris, is a thing somewhat like a person, that you can actually experience and get to know. That it, in a sense, has a unique spirit which can be likened to the theme of a symphony or literary work, something akin to a song that you can recognize and familiarize yourself with and also participate in. I haven’t been able to find the quote, but I think there’s a lot of truth here. It’s tangential to what Michael Polanyi called “tacit knowledge”, how you can access and immediately know much more than could ever be described formally or theoretically or even communicated indirectly to someone else. There’s an immediacy to this sort of knowledge that seems to bypass the senses as we understand them. It’s as if the senses are only pathways or connections or maybe doorways for our consciousness to enter into communion with the thing or person known, such that what we can reduce to sensory experience or sensory information is only ever the surface level of this profound and mutual interpenetration. This deep and incommunicable tacit knowledge.

On this little trek, I passed by two immense and strange white towers, just piercing straight up into the sky. One at the end of Ogikubo in Suginami, and the other just around where Setagaya begins, five miles further down the road.

They look like some sort of combination of lighthouses or observatories, narrow like very large smokestacks, and I have no idea what they’re for. The ocean is many miles away.

Two days prior, I went with a friend to an exhibition of the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico’s work, a lesser-known influence of the surrealists. Surprisingly, it was a really unsettling experience. Much of his early worked focused on the dehumanizing impact of technological and industrial society, about its unique manifestation of death, the particular thanatos or death drive of the modern condition. A key expression of this focus was the portrayal of mannequins as the un-becoming of the rational self, these not-quite automatons, often in somewhat sardonic parodies of various roles from Greek mythology, and in relation to absurd and meaningless architecture.

He also painted a lot of towers. This is one of his earlier pieces, I think it’s from the beginning of what’s known as his “early metaphysical period”. I don’t really agree with how they used the concept of metaphysics, seems it was a marketing concept or buzzword for its time, but there’s a lot of symbolic connotations that connect with Nietzschean thought and the existentialists in general, and there’s a psychoanalytic dimension in Chirico’s work through the conscious and explicit invocation of dream-states.

This tower is both Nietzschean and Freudian. It’s a pointless expression of power, with no obvious function and an almost absurd aesthetic. It has a dreamlike quality through the skewed lines and alien sky, and involves the two colors most significant in Freud’s Die Traumdeutung (1899) which was all the rage among young pretentious intellectuals in the pre-war years when this was painted. As was Henri Bergson, for that matter.

Back in what Americans would call jr. high school, a friend of mine was frustrated with what he called the “feminist insistence on calling missiles phallic”. How else would they look, he asked, as if the missile, the weapon of war, was just a fact of nature that carried no ideological bias an emerged just as a matter of the course of civilizational development. His point seemed reasonable to me at he time.

We didn’t get that even building them at all was a clear caricature of male agency. A simplified and dehumanized expression of phallic power manifest in a structure of oppression, violence and exploitation.

I think much of the surrealists work was therapeutic. It doesn’t seem to me that they were celebrating the absurd as much as they were trying to come to terms with the unique and inhuman form of death inherent in the framework of industrial civilization. The unbecoming of the human subject, reduced to cogs in a machinery or interchangeable numbers, disintegrated ontologically through secularization and materially and relationally through alienation.

They were trying to come to terms with the pointless expression of power of modernity, lumbering and immense. Chirico saw it in vivid detail early on, and the later surrealist and absurdist movement explored its tangible consequences when it really went sour during the wars and the expansion of technological civilization throughout the colonial networks.

An absurd, nonsensical expression of power. The recurrent debacles around the Olympics are steeped in all this, and the very games themselves in their modern form are arguably little more than a ritualized battle for futile domination, market share and profits. “Both sides” of the debate reproduce the same dynamic, the socially dominant discourses force our interpretations of the “last supper” scene of the opening spectacle to either accord with a mockery of Christianity, or a celebration of commodified and medicalized diversity. There are no other options in the discusive framework. No nuance whatsoever.

Same with the mediatic framing of the women’s boxing drama. Either you side with the reductionist perspective that women aren’t really real in the deeper, metaphysical sense, or you revert to the position implied by the character and meaning of modern athletics that women’s sports are simply inferior. You get this simplistic binary whose seeming opposites give you more or less the same outcome.

A meaningless exercise in power. Perfectly illustrated by the two victories of significantly advantaged competitors.

Late afternoon, I arrive at the “Setagaya murder house”, if one might use such a cold and sensationalistic expression. It’s a strange location, uncanny in the fullest sense of the word. The park is a little too shady in the low, orange sunlight, it’s a bit overgrown and has something slightly sinister about it, even without the context of the background events. There’s a ball court next to an area for skateboarding, just opposite to which sits a children’s playground. And behind this playground, like some unfunny joke, towers this ominous monument of death and destruction, a darkened, derelict siamese twin of a house.

It’s the last remaining building of an area which was set for redevelopment back in the late 1990s, and the family had just agreed to sell when the unthinkable happened.

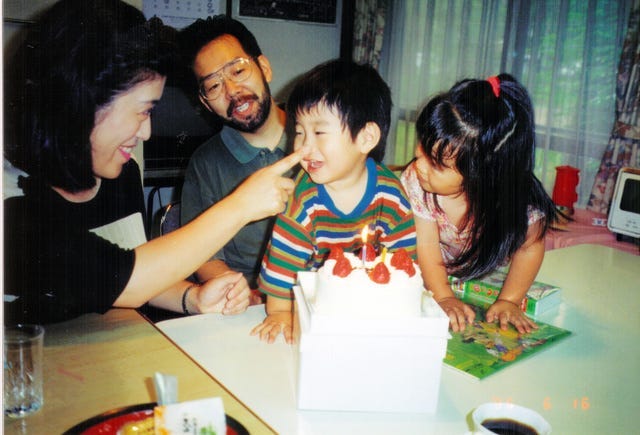

I sit down for a minute, taking the picture above and finishing the last of the water I carried with me. It’s very hot, and I still have to walk all the way back, so I don’t stay very long. But when I sit there, it slowly hits me. I feel like the kids at the end of Stephen King’s The Body, when they finally find the missing boy and are faced with realities deeper and more terrifying than they ever imagined.

For right there was death, lurking just behind the vines and a wall of chipboards recently erected by the police to prevent unauthorized high school excursions. Death in modernity’s guise as the meaningless expression of power. As the twisted outcome of alienated humanity - but also as a symbol of authority. Of hierarchy. The ghastly memorial must namely stand, must cast its uncanny shadow like a permanent blemish, like a festering sore, until the perpetrator has been found and prosecuted, and the transgression of the state’s supreme role as arbiter of life and death has been repaired.

I think we should understand a lot of the work of the surrealists as an attempt to come to terms with this senseless violence and its unique modalities. That they tried to face it, to bear it in all its incomprehensibility, and to help carry us through our own collective breaking-point to move forward.

And in looking at Chirico’s later work, it seems to me that he eventually came to the realization that we aren’t really mannequins. Or that even if you reduce human beings to automatons or soulless props, they inevitably come back to life again, with an agency of their own. His generation was perhaps overawed by the impact of the reductionist worldview, of simplistic determinism and the seemingly inexhaustible powers of the industrial and capitalist mode of science to explain and dominate reality itself. But he saw the mask slip already then, and we’re not as impressed anymore, and well acquainted with the emptiness of many of the empty promises of technological civilization.

I don’t know how we should deal with the contemporary iterations of modernity’s meaningless expressions of power and violence. But I think we have to assume something like what I deem to be Chirico’s conclusion above as a starting-point, I think we have to avoid the fatalistic appreciation of the processes of modern civilization’s death drive as an immutable and lumbering leviathan, and realize that at the heart of it all, that in the end, there’s always human agency. That there’s always choice.

And that there’s always accountability.

https://youtu.be/4USmK90GfDA?si=PIKQ_t3dZ7sB9ShP

Excellent piece, Johan. Thank you for writing. It's as if the murders weren't meant to be solved as some kind of statement to the nihilist absurdity of the modern world. Framing surrealism as therapy puts it in context coming from the trauma of WWI. But the murders seem to have none of that, they're just simply left there for all to see. Maybe it's unique to Japanese culture, but I'm not so sure.