Notes on AI as the religion of secular hyperreality

Part 1: The synthetic sacred space as the origin of secularism

Hyperreality is an outgrowth of mass communications technology.

As Jean Baudrillard uses the concept, it refers to a mediated mode of experience that is “more real” than everyday life because it’s just that much more vividly experienced. Its meaning is distilled, hyper-focused and unambiguous, and it’s generally accompanied by spectacular and enticing sensory perceptions or intellectual distractions, such as those of music or imagery. For that reason, whatever is convincingly expressed in this hyperreal mode will tend to displace the mundane, and become a crucial point of focus for the spectator. This is obvious in relation to anything from the Beatles-craze phenomenon to the impact of mass produced novels in the 1700s exemplified by the “Werther mania”. In a sense, the Sturm und Drang movement and in extension the entire era of Romanticism can be seen as an outflow of the unique kind of hyperreality catalyzed by the mass communications technology of the printing press.

But why is this important and what does it conceivably have to do with today’s artificial intelligence phenomenon, or even with religion?

Well, my basic tentative idea here is that hyperreality essentially is a kind of synthetic “sacred space” that uniquely competes with and destabilizes traditional forms of religion. I think this is the secret of secularization hiding in plain sight. It has been touched upon for centuries, and everyone knows that technology and print media played a crucial role for secularization — but I think the exact reason for the emergence of the secularization process is closer to McLuhan’s emphasis on the impact of the form rather than to the exact content reproduced through the new media technologies.

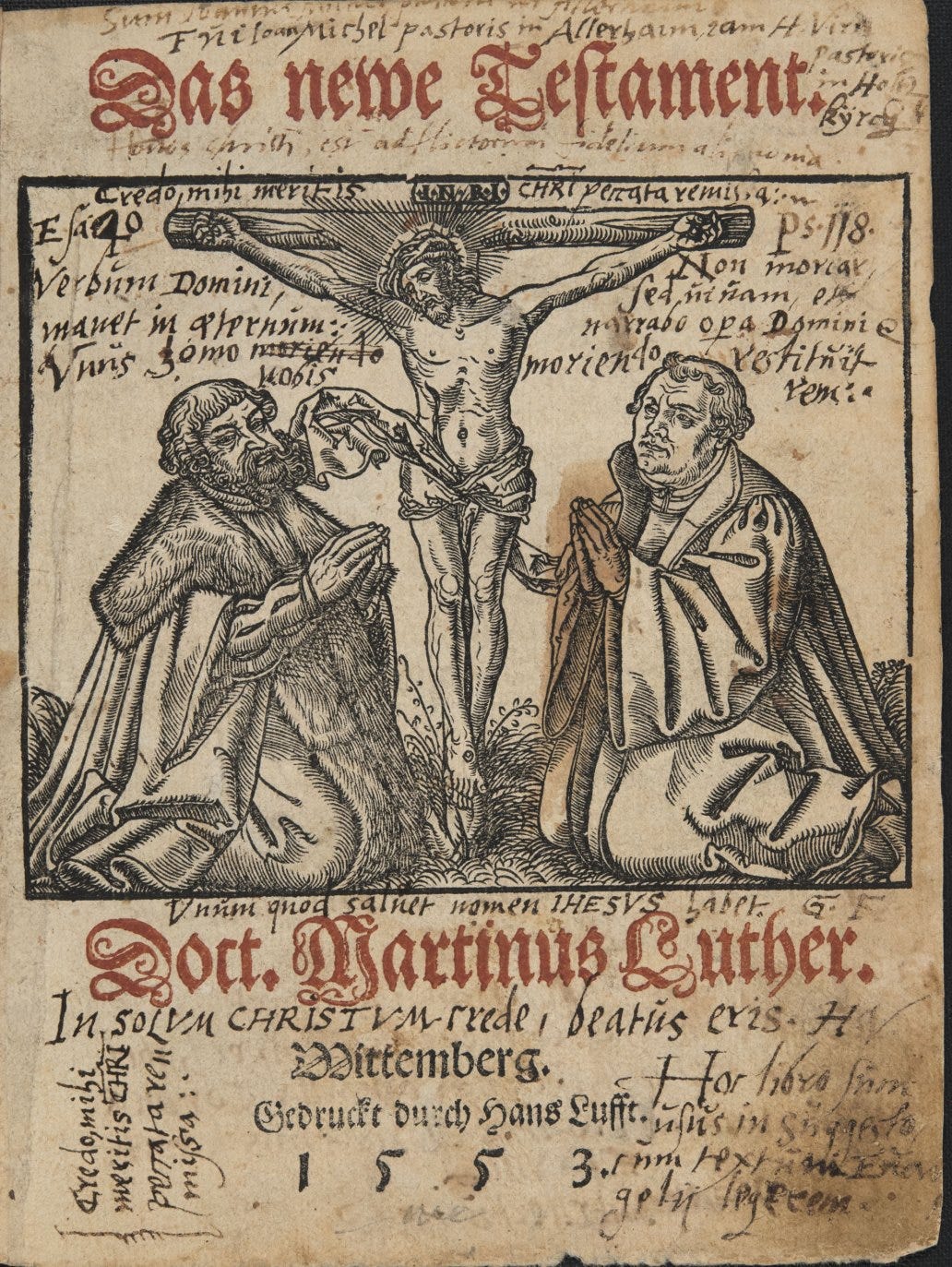

So when the Protestants and the Gutenberg Bible shattered Catholic Christendom in concert with the rapid expansion of the spectacular mass communications media of the time, a Pandora’s box was opened that enabled a synthetic analogue of the “sacred space” of religion that could now be conjured up around pretty much anything fed into and rapidly reproduced by the information machinery.

The sacred space in Eliade’s theories of religion

What I would call the “organic sacred space” is basically what the Romanian scholar of comparative religion Mircea Eliade designated as the unique experiential framework that occurs in the context of religion, ritual and spirituality. Its significance lies precisely in how it constitutes something radically different from the mundane everyday realities, and how it connects the human being to something beyond the time and space of ordinary waking life through an immediate experience of his or her culture’s motifs of myth and deeper layers of symbolic meaning.

The sacred space and the experience of the ineffable

In Eliade’s view, this sacred space is a common and defining aspect of religion as a historical phenomenon, and he emphasizes how, within the framework of religion, builds on a formative and ineffable experience or intuition of the sacred. An irreducible, lived experience of “the numinous”, as Rudolf Otto has it, or in some sense of the transcendent in itself.

But this “sacred space” should be strictly distinguished from the formative and constituting intuition or experience of the numinous — the two are not the same thing. The primordial intuition or experience of the sacred as such is the root and cause that holds everything together, the source of the meaning and symbolic significance that gets communicated and reproduced in the social and communal reality of the sacred space.

So the sacred space is a kind of tangible discourse that gets reproduced by ritual, song, storytelling, liturgy, strategic use of scenery, natural surroundings and colorful images and so forth. And you can participate in the sacred space, you can experience being transported from your everyday reality, beyond its space and time, without also actually having the immediate and irreducible experience of the numinous, of the sacred-in-itself.

In other words, you can very well partake experientially in the sacred space without actually having what is known as a “religious experience” — even though the sacred space is in a sense ultimately a secondary effect of religious experiences, and is also intended to open you up for the possibility of the numinous intuition of the mysterium tremendum. The sacred space as an experiential mode emphasizes the fruits of others’ religious or numinous experiences and the rational and intelligible truths of religion, it connects you to primordial existential realities, and is intended to open you up for your own immediate intuition of the transcendent, but it’s not the same thing as such an intuition.

And this distinction is crucial, since it enables us to think about the difference between something like an organic and a synthetic sacred space, where the latter is just a simulation of the former, lacking its connection to the numinous and transformative experience that an organic sacred space is ultimately designed to capture, translate, communicate and reproduce.

We could perhaps even talk about organic vs. synthetic hyperrealities, since both kinds of “sacred spaces” are forms of special discourses based in certain techniques for focusing and shaping thought and perception, but I’m wary of this approach since it would obscure the radically mediated nature of the hyperreal, and also risks imprinting a tinge of technological artificiality to the religious behaviours that I’d argue are a natural and primordial aspect of the human condition.

Secularism and the synthetic sacred space

So my hypothesis is that the root cause of secularization (the privatization and marginalization of religion and the ostensible suppression of religion in the public sphere) is the proliferation of competitive, synthetic, and secular sacred spaces in the wake of the emergence of mass communications media. This is not a terribly contrarian perspecive, since historians of religion, science and technology are in full agreement that the printing press synergized with Protestantism and the expansion of early capitalism towards the destabilization of traditional religious authority and the emergence of a reductionist and secular worldview.

But I’m running McLuhan’s old argument on top of Baudrillard here, and taking it a bit further in terms of historical development in an attempt to further explain exactly why society took such a rapidly secular turn in the modern period, and why post-Reformation Christianity was uniquely unstable.

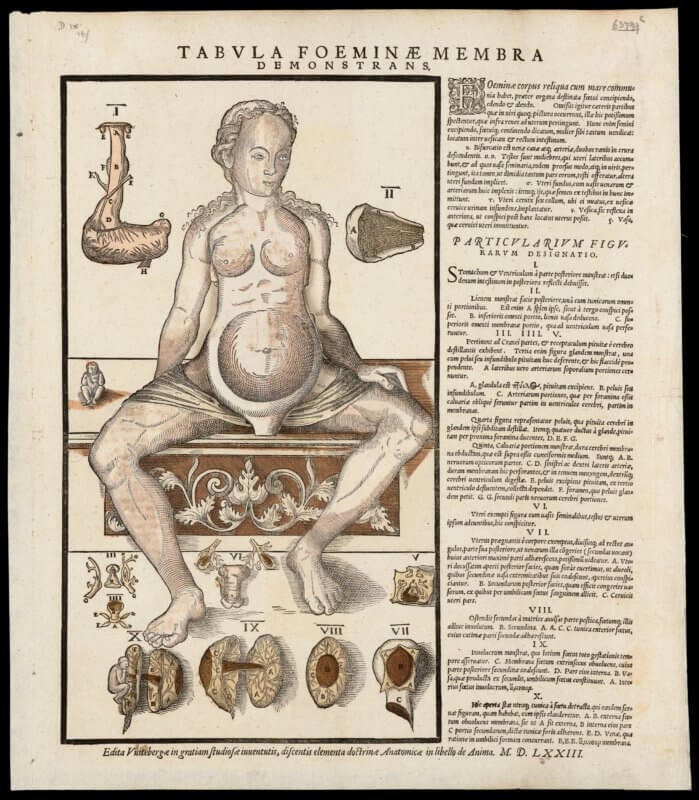

What I think happened back in the 1500s is basically that the spectacular mass-production of vividly illustrated scripture, pamphlets and theological treatises that accompanied the early reform movement enabled the formation of a private space for the consumption of mass-produced cultural products. Before this time, people didn’t read pulp novels or magazines or even send garish postcards back and forth between each other, so the sudden emergence of vividly illustrated printed material was a hugely transformative event comparable to the spread of cinema or television.

The reception of this mass production was also accompanied by the Protestants’ new and radical reevaluation of the meaning and significance of sacred scripture, a process which very likely was also catalyzed by the strong, spectacular impact of the printing technology. Here was the printed word, black on white, the gunpowder of the mind, infused with a spiritual significance like nothing else in the created universe, framed as the unique pathway of communication between the believer and the divine.

And this was the atmosphere around how the printed word was spread across Europe. This was the conceptual framing of an already powerfully spectacular mode of mass communications technology, which inevitably also became a template for how people came to approach printed material in general, outside of the framework of religion and spiritual matters.

So the technology brings the tangible potential for creating a hyperreal experiential space, and this function is uniquely catalyzed by the Protestant innovations in terms of the new role and meaning of mass-produced sacred scripture as a bearer of absolute truth discernible by the individual believer.

Tension with religion

But why does this eventually tend in the direction of secularism rather than anything else? Couldn’t the new technologically mediated hyperrealities just as well have benefitted traditional and emerging forms of religion and catalyzed their entrenchment and spread?

Now this is a crucial question for the argument I’m trying to make here, and my position is that the hypereal will be inimical to traditional religion over the long term, even in these relatively modest primordial forms that appear in the 1500s.

To be sure, not least Protestant Christianity rode on a wave of printed material and spread throughout the globe within the framework of the British and Dutch empires, and from the start, there was a significant symbiosis between the expansion of dissident forms of Christianity and mass communications technology in ways that endure even into the 20th century.

However, Protestantism and related forms of dissident Christianity are closely intertwined with secularism as a phenomenon. This is a complex discussion on its own, but the seeds of modern irreligion are clearly present in certain key innovations of the early reformers. The radical individualism expressed in how the believer becomes their own religious authority, which on a grander scale is represented by the usurpation of papal jurisdiction by the local European monarchs, is nothing less than the privatization of religion as uniquely fostered by the new personal hyperreality of the printed word.

And when the monarchies along the very same lines set out to design a new model of the state that cedes none of its sovereignty to Rome whatsoever, that’s precisely the birth of modern political secularism. The division between the profane and sacred realms that had been a core part of Christianity since the early church now becomes an institutional cornerstone of the emerging modern state.

The culure and he ideas reproduced in this separate secular realm are then inevitably placed in a structural competion with that of religion — and also catalyzed and reinforced by the characteristics of the new experiential mode brought about by mass communications technology. The hyperreality, the synthetic sacred space.

And I would argue that the novel hyperreality is inherently going to tend towards this kind of structural competition with or marginalization of religion for a number of different reasons.

First of all, this new synthetic sacred space is radically private, or at least potentially so, in a way that starkly contrasts with the communal and relational character of the rituals of traditional religion. It inherently fosters a separation and an isolation of the individual, and a privatized experience of meaning and symbolic significance of precisely the same kind that gets expressed in the Protestant emphasis on individual piety, conscience and a privatized relationship with the divine.

And this means that this new synthetic space of meaningful experience is no longer necessarily bound by the communal and perennial values of traditional religion, but can indeed emphasize and reproduce whatever inkling of passion or desire the solitary human being happens to succumb to.

And you, amiable debauchees, you who since youth have known no limits but those of your desires and who have been governed by your caprices alone, study the cynical Dolmancé, proceed like him and go as far as he if you too would travel the length of those flowered ways your lechery prepares for you; in Dolmancé’s academy be at last convinced it is only by exploring and enlarging the sphere of his tastes and whims, it is only by sacrificing everything to the senses’ pleasure that this individual, who never asked to be cast into this universe of woe, that this poor creature who goes under the name of Man, may be able to sow a smattering of roses atop the thorny path of life.

De Sade (1795). Philosophy in the Bedroom.

In other words, the hyperreal can in principle emphasize and reproduce ideas, narratives and meaningful experiences without regard to material, relational, ethical or doctrinal limits. Such a versatility of the new media landscape will also indirectly pose a disadvantage for worldviews and ways of life that cannot make effective use of it.

Those worldviews and ways of life whose meaning depend on a communal exchange or complex relational connections such as profound religious experiences will not be able to make effective use of the technologically mediated hyperreal as a synthetic sacred space without risking a loss of meaning and cohesion.

And the traditional ways of life suddenly face competition from every direction in this new environment, since any worldview, ideology or social trend now has access to an analogue of the sacred space that can be accessed basically anywhere. On top of this, the framework, the arena for competition is also the emergent secular state, itself partly a product of the new mass communications technology, and which disproportionately promotes non-religious worldviews.

So to sum things up, it seems to me that the hyperreal, considered as a “synthetic sacred space”, has three major differences in relation to what I would consider an organic or traditional form of sacred space.

1) First, the hyperreal does not operate with regard to a transcendent reference-point for the renewal and revitalization of meaning, which in Eliade’s view is just the very foundation of a sacred space. Mass communications technology can of course reproduce religious themes, the point is just that the spectacular hyperreality isn’t structured around a stable distinction between holy and profane, derived externally from the ineffable experience of the sacred. The hyperreal is based around turning up the volume on spectacular and enticing sensory perceptions, imaginations or even intellectual pleasures, and its meaning is shallow and sterile, inherent in and limited to the immediate impact on the spectator.

2) The hyperreal, on the other hand, lacks limits in another sense. It’s not bound by ethical, material, relational or other crucial external factors in terms of what it may reproduce. In the 1500s, this is almost purely a potential attribute, but this aspect becomes increasingly prominent, especially through the developments in communications technology that progressively diminish the importance of space, time and context, until we finally arrive at Baudrillard’s “virtual” — an experiential space which is disconnected from any actual referents and from any represented tangible realities.

3) The hyperreal also lacks a distinct purpose beyond itself, which is not least exemplified by the “virtual” character, its non-representative nature and lack of reference to any actual and tangible realities. So the hyperreal as synthetic sacred space isn’t “about” anything else apart from itself, and its meaning is contained within the horizon of the experience, unable to actually transcend the immediate and contingent.

One could perhaps say that the hyperreal brings about a kind of simulated transcendence, enhancing and sharpening the sensory appetites and the lower intellectual pleasures to the extent that they seem to constitute a reality unlimited by time, space and the mundane everyday life.

Whence the possibility of an ideological analysis of Disneyland: digest of the American way of life, panegyric of American values, idealized transposition of a contradictory reality. Certainly. But this masks something else and this "ideological" blanket functions as a cover for a simulation of the third order: Disneyland exists in order to hide that it is the "real" country, all of "real" America that is Disneyland (a bit like [how] prisons are there to hide that it is the social in its entirety, in its banal omnipresence, that is carceral).

Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology) but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real, and thus of saving the reality principle.

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacra and Simulation.

So the hyperreal, this “experiential space” that mass communications media structures around the “consumer”, our new and diminished form of human being called forth by modernity, is really a sort of macrocosm of the Cartesian individual. It’s a radically separate sphere of consumable and commodified meaning, independent to the solipsistic extreme, and cut off from any external and persistent sources of meaning or transcendent truth.

But this also provides a significant competitive advantage in the “information ecology” of the emergent mass culture, especially in comparison to traditional religions, since this new, synthetic sacred space does not have to rely on nor pay any dues to the indomitable sacred.

For the above reasons, which have not really entered much into the historical or sociological analysis of secularization, I think that over time, mass communications technology will strongly tend towards the emergence of what we know as secular worldviews. Due to the structurally inevitable character of the new hyperreal experiential spaces as competitors to the organic sacred spaces of religion, mass communications technology will indirectly favor secular worldview content.

And this is of course in line with the historical record, and whether or not I’m right about how all of these factors interact in practice, mass communications technology does seem to reinforce secularization independently of the coherence of the actual ideas conveyed.

Going back to the 16th century, the printed word now enables a privatized sacred space in the personal sphere of the individual, crystallized around the ritualized experience of possessing objective truth or authentic experience. And when this gets extended into the broader realm of non-religious discourse, we then see the development of the primordial hyperreal as a technologically mediated experiential space. A truth transcending space and time, ritually and spectacularly conveyed by the written word through the practice of focused reading, becomes the focal point of the print culture of modernity, whether in terms of reductionism, quantification and scientism, or of the radical subjectivism of the romantics and the postmodern when the pendulum swings back. Both extremes imperial, Faustian and solipsistic in their own ways.

And in the background of this process, the importance of the innovative Protestant principle of sola scriptura, “by scripture alone” is almost impossible to overstate. It has an incredibly profound impact on the later development of Western culture, identity and intellect all across the board. Sola scriptura sets up this ideology of the primacy of objective information that can be contained and expressed in language, such that all of reality and its foundations can be fully translated into definitive, objective, authentic and scientific descriptions without any remainder, without anything being lost in this translation.

And what almost nobody except maybe Adorno seems to have realized — this emphasis on an individualized and detached consumption of objective information holds for both sides of the spectrum, whether we’re dealing with quantifiable scientific knowledge or rather with the qualitative authentic experience of the Romantic reaction (and of the Nietzscheans, existentialists and postmodernists).

So both the quantifying and reductionist realm of modern science, as well as the enduring antithesis, the emotional and subjectivist reaction, are structured around a Protestant theological doctrine that in turn was born out and synergized with the cultural impact and reception of the technology of mass communication and mechanical reproduction.

All of it is secular, solipsistic, Cartesian, and predicated on a technologically mediated hyperreal mode of privatized experience.

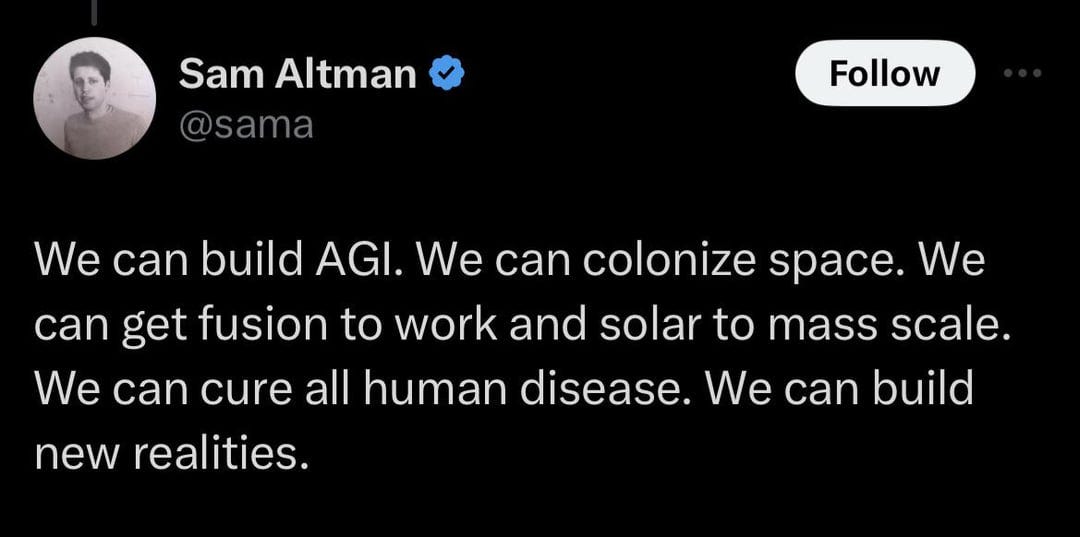

Next week, I’ll discuss how the contemporary AI-phenomenon and the new kinds of reverential personal attachments we see emerging around its relational modes of interface, argubly is the coming full circle of the entire process of secularization that began back in the 1500s. The core idea is how the process seems to validate all of the legacy myths of the secular worldview through a new kind of synthetic sacred space that provides an approximate hyperreal emulation of religion, and which may sit on a more enduring supply of meaning.

No.

No. It's a mystery. A man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with.

He can know his heart, but he dont want to. Rightly so. Best not to look in there. It aint the heart of a creature that is bound in the way that God has set for it.

You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it.

You believe that?

McCarthy, C. (1985). Blood Meridian.

Well, that got me thinking. But that's the purpose of your writing, or one of them.

Isn't the current state of globalist theocracy merely a substitution of higher meaning with the secular profane? Where instead of papal authority or God-guided monarchy we have a post-modern religion with its occult high priests in the shadows, its NGOs, its public persona of celebrities and politicians, its idol worship/fetish of devices. And underlying that profanity, could it not be Evil itself?

In other words, don't we already have a world religion, albeit subverted and corrupt?

I suggest the entire reason of the hyperreal is to gradually dislocate us not just from physical reality but from our bodies - to have us as captured consciousness enslaved in a digital Matrix where we experience life as a fully-controlled and curated hyperrreality, a synthetic 'sacred' space. While the occult priesthood and their chosen ones have the world and all its bounty to themselves.

That seems to be the trajectory to me, what with the Bio-Digital Convergence and the Internet of Bodies and walking around seeing most people with their heads in a screen.

When I see what these so called geniuses claim and fail to accomplish, I'm reminded of Ian McGilchrist's book The Matter with Things. He explains how being left hemisphere biased leads to a lack of seeing reality as a whole but obsesses over the parts, like a machine.

https://robc137.substack.com/p/left-brain-vs-whole-brain-in-battlestar