So in the last piece, I left off with how United Fruit exemplifies the basic template of how the West dominates its resource colonies and foreign manufacturing assets.

As a brief recap, the United Fruit Company was a major US corporate entity founded in 1899. In the mid 50s, it controlled the economies and the political structure of six major South American nations through the banana trade. It controlled the best arable land of these nations (bananas are known as “heavy feeders”, they’re pretty difficult to cultivate and need good and nutrient rich soils). United Fruit, nested in the upper echelons of the US corporate structure, basically owned these states, reminiscent of how the East India company used to literally own Hong Kong and major parts of the Indian subcontinent as a proxy for the British crown.

Attempts to reestablish popular control over Guatemala’s agricultural assets were met with extreme prejudice, resulting in the CIA staging a coup to install a military dictatorship.

While this isn’t always the outcome, since most of the third world export economies cannot readily mount a cohesive political resistance to foreign domination, the basic template of control holds true in almost every single instance.

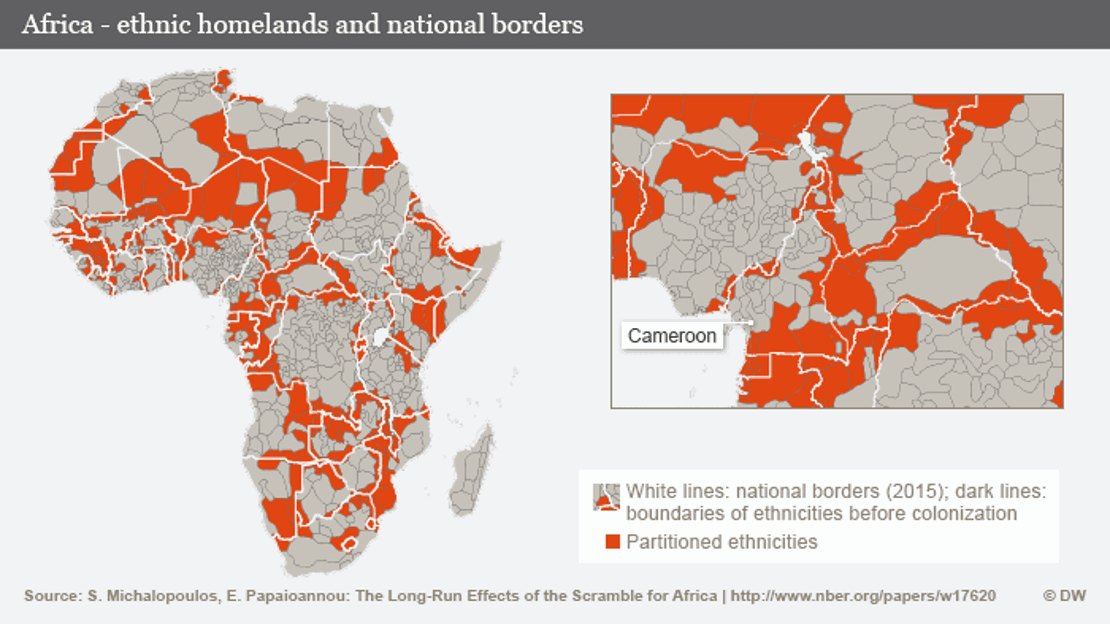

To begin with, the basic structures of colonial exploitation erected between the 1500s and the 19th century completely ruined indigenous economies, systems of producing and relating to nature, as well as institutional ties and political structures. These polities were more or less forced back to the level of subsistence economies, while also being decimated by artificial ethnic conflicts brought about by colonial expropriation.

Almost nobody knows that carbon steel was produced in Sub-Saharan Africa more than 2000 years ago, or that Axumite civilization was one of the great powers of Classical Antiquity, with its political centre in today’s Ethiopia. Examples abound.

This background incidentally also meant that when industrialization reached the “third world”, generally in the 20th century, it was exclusively through major Western corporate entities in search of base resources for exploitation and for delivery to markets in the developed world. This created a parallel economy of exploitation that due to its structure could not be fruitfully integrated in the surrounding societies, so the technology and wealth produced couldn’t properly “trickle down” into the fundamental economy below. This left the “third world” in a permanent state of subjugation coupled with persistent capital incentives.

There are multiple structural reasons for this.

The major corporate entities employ comparatively advanced technological equipment which is sourced from abroad, and tend to bring their own employees, not least since there’s a lack of preferentially skilled workers among the indigenous population. They get stuck in menial positions at best.

The global supply chains inherent to the foreign technologies render them inimitable at the local level, so they can’t effectively stimulate an indigenous counter-industrialization from below (as was the case with European industrialization among relatively equal competitor states).

Finally, and what’s probably most important, the multinational corporate entity that exploits labour or resources in the third world cannot, even if its board or shareholders would like to, prioritize the interests of the host nation. The multinational is beholden to foreign centres of power on the other side of the world, where its main depositions and investments are also firmly situated. The international market rather than local interests is the main factor determining the character and size of the corporation’s production.

In other words, corporate strategy cannot regard irrelevant local problems where the business is established, but must adapt to the global realities of the particular type of enterprise in which it’s involved. So the oil company exploring off the coast of Namibia isn’t going to reinvest its profits in childrens’ hospitals or local organic farming, but will funnel its gains into whatever it is that brings immediate shareholder returns, such as additional prospecting in Indonesia or the expansion of refining capabilities back in the US. So basically, the profits will naturally go towards further exploitation or reinvestment in wealthy nations, since here’s where you can reasonably expect immediate returns on investments.

So there’s a Faustian bargain involved for any export-dependent third world nation that finds itself being “modernized” under the auspices of a major Western multinational.

For all the immediate benefits involved, sweetening the deal, the end result is a stultification, a long-term stagnation of a kind that structurally undermines economic and political independence. This situation is of course exacerbated by the fact that these multinationals are integrated in powerful global conglomerates supported by the first world in various ways. And as the United Fruit example (and my last post’s list of interventions) so clearly shows, they will not stop at genocide to produce a local political climate beneficial to their interests.

If people select the wrong sort of government, another, more appropriate one, can quite easily be selected for them.

This overarching framework of order is known as “free trade” and “the open society”.

The U.S. conception of “open access” is marvelously expressed in a State Department memorandum of April 1944 called “Petroleum Policy of the United States,” dealing with the primary resource. There must be equal access for U.S. companies everywhere, the memorandum explained, but no equal access for others.

The U.S.-dominated Western Hemisphere production (North America was the leading oil exporter until 1968), and this dominant position must be maintained while U.S. holdings expand elsewhere. U.S. policy, the document asserted, “would involve the preservation of the absolute position presently obtaining, and therefore vigilant protection of existing concessions in United States hands coupled with insistence upon the Open Door principle of equal opportunity for United States companies in new areas.” That is a fair characterization of the famous principle of the “Open Door.”

(Chomsky, N. (1986). Power and Ideology: The Managua Lectures.)

Most of the time, however, the carrot goes a long way. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (the IMF) are key factors in this regard. The World Bank was originally founded to provide institutional support for the reconstruction of Europe after World War 2, and the IMF was intended to stabilize the international financial system and shield it from undue currency fluctuations. Both were created at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, and are based in Washington, D.C.

However, the World Bank rapidly became an institution for marketing structural loans to former colonies in the third world, generally in concert with the modernization of local infrastructure to serve the interests of extractive multinational corporations. So these loans were used to finance infrastructure projects either to support the parallel economies of exploitation established by the foreign corporations, or to unlock further resources and labour for future extraction of wealth through indebtedness.

In other words, the World Bank marketed loans to support expansion beyond the means of the third world countries’ export earnings, which further exacerbated the basic Faustian bargain described above.

So now, you have a situation where it’s not just that corporate profits won’t return to the local economies - there’s also the added aggravation that these neo-colonies will have to service ever-increasing amounts of debt owned by the very same Western corporate structure that’s exploiting their resources and human capital. And of course, any “modernization” or expansion is going to take place under the auspices of the Western major multinationals, so the loans are really just immediate liquidity funnelled right back into the pockets of the same power structure that just sold them to you.

And your people are the ones who pay for it. All the way. They pay for their own exploitation. They pay for the expansion of foreign incursions into their own resources and political and economic sovereignty.

If you happen to be a local leader who chooses not to take the cash? Yeah, that’s unlikely to end well for your and your family.

And all of this is really far from a conspiracy in any conventional sense. It’s an emergent effect of how power is being organized in the framework of the modern political and economic project. Allegedly, even J. P. Morgan himself was appalled when learning of what his Pinkerton goon squads had been up to. Still seeing himself as a small businessman, and lacking detailed oversight over all the institutional processes he indirectly managed, he couldn’t really fathom the nature and character of the powers that had been unleashed, and nominally was under his control.

Others probably could fathom quite a good deal of what was going on.

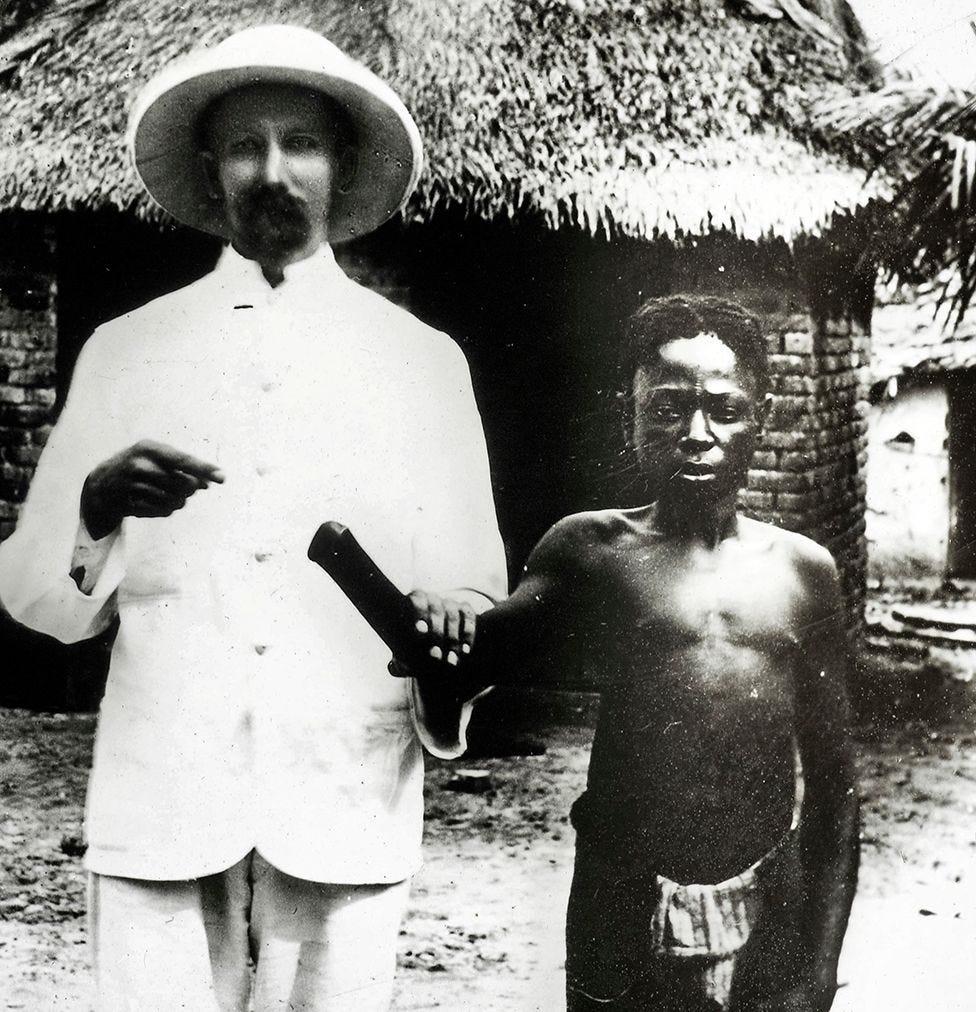

This entire framework of order is of course steeped in racism at all levels. It’s the predominant historical manifestation of racism in every respect, and indeed, its colonial foundations are a root cause of the entire modern social construct of racism, and the way in which it developed from its early origins (e.g. the blood purity statutes of pre-colonial Spain).

This makes the contemporary liberal order’s vehement focus on rooting out racist ideology and hate speech utterly hypocritical.

The system, of course, is only interested in suppressing manifestations of racism that can threaten its stability or interests, and is therefore quite ready to clamp down hard on any disruptive racist ideologies that might hamper the smooth operation of its imperial machinery. At the very same time, it’s structurally dependent on the violent subjugation and exploitation of racialized populations in the third world.

And this little discrepancy segues neatly into how the soft power of imperial propaganda works towards undermining meaningful dissent, especially in the post-9/11 era. I’ll focus the next instalment on this particular issue.

If to preserve political independence and civil freedom to nations, was a just ground of war; a war to preserve national independence, property, liberty, life, and honour, from certain universal havock, is a war just, necessary, manly, pious; and we are bound to persevere in it by every principle, divine and human, as long as the system which menaces them all, and all equally, has an existence in the world.

(Edmund Burke. (1796). Letters on a Regicide Peace.)

Excellent piece.

Thank you for this concise piece.