Habitat, the original 1986 "metaverse"

The other day I realized that that it’s almost 21 years since World of Warcraft launched back in 2004, which kind of boggles the mind.

I never played it myself, but couldn’t escape the impact of the phenomenon. WoW, as the first really successful MMORPG is also connected to the establishment and entrenchment of social media in general, expanding its user base years before something like Facebook was widely adopted. Something like a quarter of a billion people in total having have played it worldwide.

And World of Warcraft is still up and running, receiving regular expansions with several millions of regular subscribers, even though it peaked around 2014 or so.

Digging around a little bit, however, I found that this is also true for the much older EverQuest, which originally launched in 1999, and which had a peak subscriber count around 2004 with something like 500 000 active players. Remarkably, more than a quarter of a century after its release, that count is still around 30 000 or so.

So I sat there, trying to wrap my head around the fact that this just recently so fresh and fascinating phenomenon of the MMORPG was now not only more than 25 years old, but those same progenitors of the genre were still the main contenders.

In a media field that used to change so rapidly, this is sort of like if Pong would still have been one of the most widely played sports video games in 1997.

But after doing some additional research, I stumbled upon something that, at least from my skewed perspective, is nothing short of astonishing.

The MMORPG phenomenon is namely in itself derivative of a significantly older experimental game and interaction platform that combined sandbox gameplay and user customization with a full-fledged virtual community that in many ways have not yet been surpassed by later software and digital platforms.

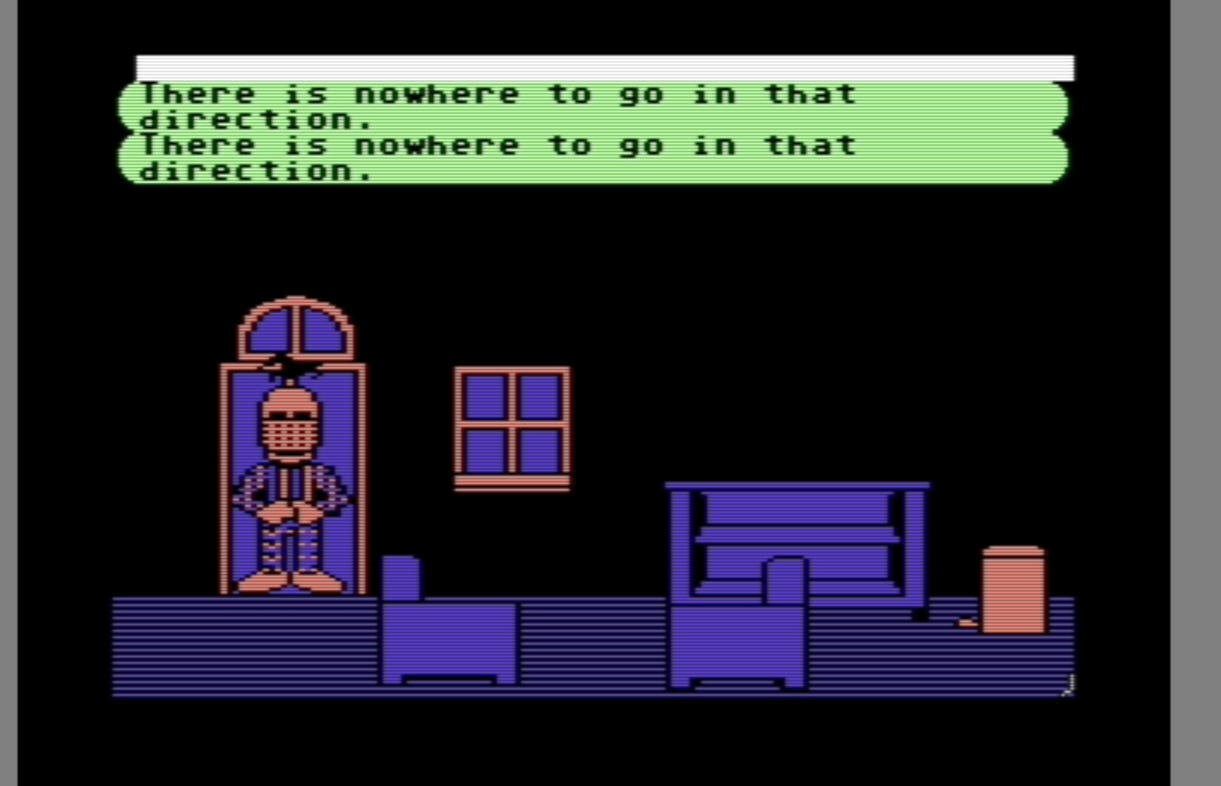

Almost 40 years ago, LucasArts ran a two-year pilot beta-test of its Habitat game, which basically was a huge MUD with a graphical interface that you connected to via the C64.

So a MUD was a text-based multi-user role-playing game, the first of which came about around fifty years ago (and we did still play them back in 2000).

These were the same type of game as the older interactive fiction adventure games, yet designed for many simultaneous users. Forerunners were well-known titles such as Oregon Trail of 1971, where you navigated the texual descriptions of an environment through simple commands.

Habitat was then an extension of the MUD that was intentionally designed to foster free player interaction and even collective content generation in an open-ended framework. It was not a traditional game in the sense that you were given a narrative and a set of goals to pursue, but rather just a vast sandbox environment with an emphasis on free player interaction as the key value.

And the unique approach that Habitat exhibited, and which set it apart from all other later iterations of the MMORPG model (with the possible exception of Second Life), was the emphasis on harnessing the creative agency of all the users involved. The environment, even down to its basic rules and the structure of the virtual world, was supposed to be a collective enterprise, with only the very foundations in terms of the programming and the underlying hardware being fixed.

The two lead designers, Chip Morningstar and Randy Farmer, expressed this approach as resisting the “conceit that all things may be planned in advance and then directly implemented according to the plan's detailed specification", further arguing that “the potential capabilities and imagination of a game would remain confined within the small niche of developers. … Even very imaginative people are limited in the range of variation that they can produce, especially if they are working in a virgin environment uninfluenced by the works and reactions of other designers".

This is an incredibly radical approach in comparison to today’s propriteary and tethered playgrounds-for-profit. It’s as if Facebook would be a collectively owned space, in every detail designed by the users themselves with the purpose of fostering the kinds of interaction they would be interested in, rather than a tool for milking advertising profits and the manufacturing of consent.

The moderators and admins of Habitat were even cornered by its own users a few times, and, astonishingly, instead of just crushing them with the banhammer, the mods actually thought it best to negotiate with the people involved, because they felt that the perspectives, intentions and goals of the users were crucial for unlocking the potential of the virtual worlds they saw emerging in the fledgling cyberspace (they unsurprisingly cite William Gibson in their papers).

Imagine that. A user-generated internet where the mods actually thought of themselves as custodians of a set of commons where the key value was to unlock peoples’ creativity and fruitful, voluntary interactions.

A pretty far cry from today’s fucking nested Skinner box designed to maximize the entrenchment of addictive behaviours for profit through operant conditioning, wouldn’t you say?

‘The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games,’ said the voice-over, `in early graphics programs and military experimentation with cranial jacks.' On the Sony, a two-dimensional space war faded behind a forest of mathematically generated ferns, demonstrating the spacial possibilities of logarithmic spirals; cold blue military footage burned through, lab animals wired into test systems, helmets feeding into fire control circuits of tanks and war planes. `Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts... A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding...'

Neuromancer.

I don’t know if something else would have been possible. As radically techno-pessimist my perspective is, I think it just might have been.

In one example from Habitat, a couple of players discovered an exploit through an unintended price difference between a few of the game’s in-world vending machines, so they sat online all night and scraped together a small fortune, which the devs discovered first the morning after when they found that the in-game currency in circulation had expanded significantly. This could have caused a problem, since people normally had to trade and barter for resources in the virtual economy, but instead of banning these users and confiscating their ill-gotten gains, the admins simply talked to them, explained the situation and found a common solution through deliberation. The users then invested much of their gains in further expanding the commons such as through launching user-created quests.

A Rock, Paper & Shotgun review of the non-game and its revival project from 2017, paying the usual lip service to progress in the digital spheres while you can clearly read the despondency between the lines, waxes nostalgically about the days when tech used to look like magic and when we saw the infinite possibilities of the emerging internet. Now I don’t care much for Arthur C. Clarke nor the surprisingly childish ethos of early sci-fi, but maybe the reason that you don’t see these possibilities anymore is because this once-promising sphere of human interaction was rapidly colonized by capital — whether or not that outcome was more or less inherent in the technological structues themselves. For what this nostalgia is really about, which also goes for the broader vaporwave vibe of contemporary culture, is a lament over alienation.

And free, unstructured play is the opposite of alienation. Whether it’s face-to-face or in the framework of some game we make up for indirect interaction, play is inherently integrative, individuating, co-creative and healing.

And it was precisely the possibilities for awakening and strengthening these forms of interaction in opposition of an increasingly alienated, inhuman and heartless society that enticed our generation so much back in the late 80s and early 90s. It really felt like another world could somehow be possible, and that we now could embark on hitherto unthinkable adventures with people across the world, uncovering entirely new nuances of human connection.

Back in 1996, when I had an e-mail penpal in New Mexico, we talked about the future as if we’d just discovered alien life on Mars, in awe of possible developments where it seemed like entirely new worlds and new tribes could emerge, free of the suffocating constraints and the damaging social environment that encroached upon us already in our early teens.

I don’t know if any of that was in any sense real, but it seems obvious to me that an internet truly operating as a commons rather than a machine for private profit and the reproduction of social hierarchies would at least be possible. Where art and play and imagination and companionship and mutual desires wpuld be the predominant values, expressed through the agency of empowered users, no longer reduced to the tethered and passive recipients of addictive propaganda.

But now, we’re in a situation where digital technologies have encroached upon human agency to the extent that we, to paraphrase Thomas Lynn, have even begun to cede our roles on stage to the hollow non-persona of the artificial agent. Where the space to genuinely act, and arguably even to authentically be ourselves in the world, has shrunken away to almost nothing.

A desolate, and empty landscape, where everything is dead and fixed in its place, ironically mirrored by the dead universe of the current reboot of Habitat where maybe one or two human beings meander, entombed in their digital avatars in search for a human connection nowhere to be found.

But we can take it all back.

Or we can smash it.

Or we can transform it into something else entirely. The possibilities are still endless.

Society’s power structures, and ultimately, the very trajectory of history itself, are what they are for no other reason than that we actively partipate in them.

And this moment, when even the content and form of our thoughts themselves are beginning to take on the immutable logic of a machine built for exploitation, consumption and domination, the power of actually thinking the ostensibly unthinkable becomes almost infinite.

It’s when art is dead that any actual art becomes a riotous, explosive rebellion.

It’s when everything seems meaningless and incomprehensible that any steadfast affirmation of truth becomes a veritable revelation.

And it’s when compassion and faith and love and kindness seem quaint and meaningless obsoletes and when they’ve build a world around us where human beings are reduced to nothing but pointless bundles of selfish genes that any genuinely decent act is nothing less than a revolution.