Beyond Descartes and Private Subjectivity

On (mostly) a relational view of consciousness, composite subjects, and common perceptions of the "external world"

(this is a writeup of the notes of my docent/associate professor installation lecture from Nov. 30)

+++

This lecture is on how reality pretty much is the way you think it is.

But we'll start at the opposite end:

How do you know that other people aren't actually zombies? How do you even know that there is anything apart from yourselves? How do you know that there is something outside of your own self, that there really is something outside of your own awareness?

This is, in a sense, the foundational question of modern philosophy, believe it or not (by modern philosophy we normally refer to the period from the 16th century and onwards).

And quite spontaneously, the vast majority of people probably say, when they come across this idea, when they come into contact with this claim that is implicitly tested by the question - most people probably think that there is something unhealthy about the whole thing. That there is something morbid in the solipsistic notion that nothing really exists except one's own self.

And I think that assessment is absolutely correct. I think that modern philosophy's almost feverish quest to find its way back to reality and get out of the dreamlike shadow world of skepticism is in many ways an expression of trauma. That this fixation on one's own self as cut off from the outside world, and the corresponding approach to the external world around us as a pile of dead, abstract and replaceable objects that we can plunder and subdue as best we like, I think we have to consider all of this as a set of unhealthy coping strategies that have emerged in a culture marked by generations of trauma.

Trauma that has to do with the enormous upheavals connected to modernity in all its aspects, not least industrialization and the radical changes in production conditions and relationships between people, and between people and the outside world, that industrialization brought about.

But this disconnect is thus in many ways the basic issue of modern philosophy. And if we raise our perspective a little bit, we see a distinct pattern of thought from the late Middle Ages until today that is characterized by this rift between the self and the world.

Historically, this movement runs from nominalism in the struggle of universals, then via the Reformation, Bacon and Descartes to Hegel, Kant, empiricism, rationalism, and out of this ideological muddle, perhaps mainly from French utopian socialism and British political economy, then grows the modern ideologies, which then end up in an historical end point in logical positivism and existentialism as a kind of diametrically opposed set of answers to this basic problem with the world outside the self - in the end we then come all the way to secularization, to the radical dissolution of postmodernism and whatever we’re supposed to call this unique condition of our time.

This movement of thought that goes through all these ideological historical entanglements is marked by one and the same basic problem which, in one way or another, consists in the fact that we have been cut off from reality and are trying to find our way back.

And the remarkable thing about the whole situation is that it is not really difficult to find convincing and definitive answers to this basic problem. For example. that the whole theory contained in the solipsistic question with which I opened the lecture - that is, how we can know that there is a world outside ourselves - the whole theory contained in this question is based on an artificial and abstract separation between the self and the world.

And this separation, this idea that here is me, and out there is the world, and that there is a deep ontological separation between the two of them that makes the world somehow less real than my own consciousness—all this is after all an artificial and rather complex theory that is superimposed on immediate reality. That is superimposed on the unfiltered existence we partake in. And there is nothing wrong with artificial and complex theories, but as soon as we say they are true and universal, ie. if we say that it would be absolutely true (and that there’s nothing we can do about it) that there is no world outside of our own consciousness, well, then this is an objective fact, something independent of our perspectives and of what we think and believe - and then we have already denied the core hypothesis.

So - already when you try to make solipsism universal, you have denied it, because then you have taken the step into a theory building that must be anchored in the absolute truths of realism.

This is a bit abstract, and I'll try to make it even more difficult for you guys –

Namely, there is also another, rather subtle conclusion to be drawn here – if solipsism is a secondary theory construction that ontologically separates the self from the world, then that theory construction must necessarily be based on some fact that precedes the separation. Some basic fact that existed before this Cartesian section was even thought of, and because a theory was said. cannot saw off the branch it sits on without falling, the perceived separation between self and world can never legitimately claim to be the original and universal condition. This distinction must therefore be about an indirect, secondary and artificial experience. We'll come back to this in a moment. (and without this fatal distinction, distinguishing objections such as "I am the absolute truth" cannot be made)

I'm going to plug in here a quote from the surprisingly unknown British philosopher Denis John Bernard Hawkins, from a 1947 book titled Criticism of Experience. And in the title of this book lies exactly what I tried to express just now - a critique of the large complex theoretical construct that lies on top of, and which interprets the immediate experience, in a misleading way. Hawkins writes - he has first spoken a little about Shakespeare and Hamlet, and continues:

Fictions are inexplicable without a foundation in reality. Primarily, then, to know is to be aware of something real, and objects of mind which are not real in the usual sense of the word are secondary and have to be explained in terms of primary objects which are unambiguously real. Knowing is, of its very nature, related to fact and rooted in fact. Moreover, it is, of its nature, a way to escape from subjectivity, from the fatality by which you are merely what you yourself are . You cannot be more than you are, but you can know things other than yourself. The thinking mind, as Aristotle profoundly remarks, is in a certain way all things.

In any case - it is not difficult to find philosophically reasonable answers to this basic problem regarding the self and the so-called external world. It is not difficult to find definitive and rationally impenetrable answers to these questions—and there are many such answers in each of the historical traditions I mention earlier, in everything from Descartes to existentialism. But the question still comes back in different ways and in new guises. Continuously.

Why? What causes this recurrence? Why is it that this experience of a separation between the self and the world is reemerging in thousands of different ways in the cultural content of industrial civilization?

That this problematic is reproduced, I argue, has less to do with the quality of the philosophical response and the rational sustainability of the responses, than it has to do with human experience, and especially our emotional experience and our highly private experiences of trauma.

I therefore argue that this experience and its philosophical expressions has to do with an ongoing traumatic process which then leads us back to a problematic existential experience which we then try to resolve or process with the help of philosophy.

The answer to the philosophical problems is thus only partly philosophical. You can say as a parenthesis that after twenty years on this job I have finally realized that we need something other than philosophy.

There is hope for everyone.

+++

But trauma, then - what is trauma? What is trauma , why does it create an experience of separation from the outside world, and why should trauma be something that particularly characterizes the human condition in modern society?

Trauma can be understood in slightly different ways, but in psychological terms it is a state of intense or chronic stress or strong negative experiences that are linked to various forms of threat, and that threat can include everything from bodily harm to various forms of integrity violations or social exclusion.

We don't really need to go into clinical definitions, but trauma is thus about some kind of psychological stress that causes permanent pain and that to a greater or lesser extent affects the individual's attitude to himself and to his surroundings. The separation from the outside world is also complex, but it can be seen as the individual limiting her openness and vulnerability to the environment which is threatening and which has harmed her. All trauma is really relational in nature, and in various ways has this separation as a major component.

And perhaps you can therefore also say that pure separation is deep down the root and core of trauma.

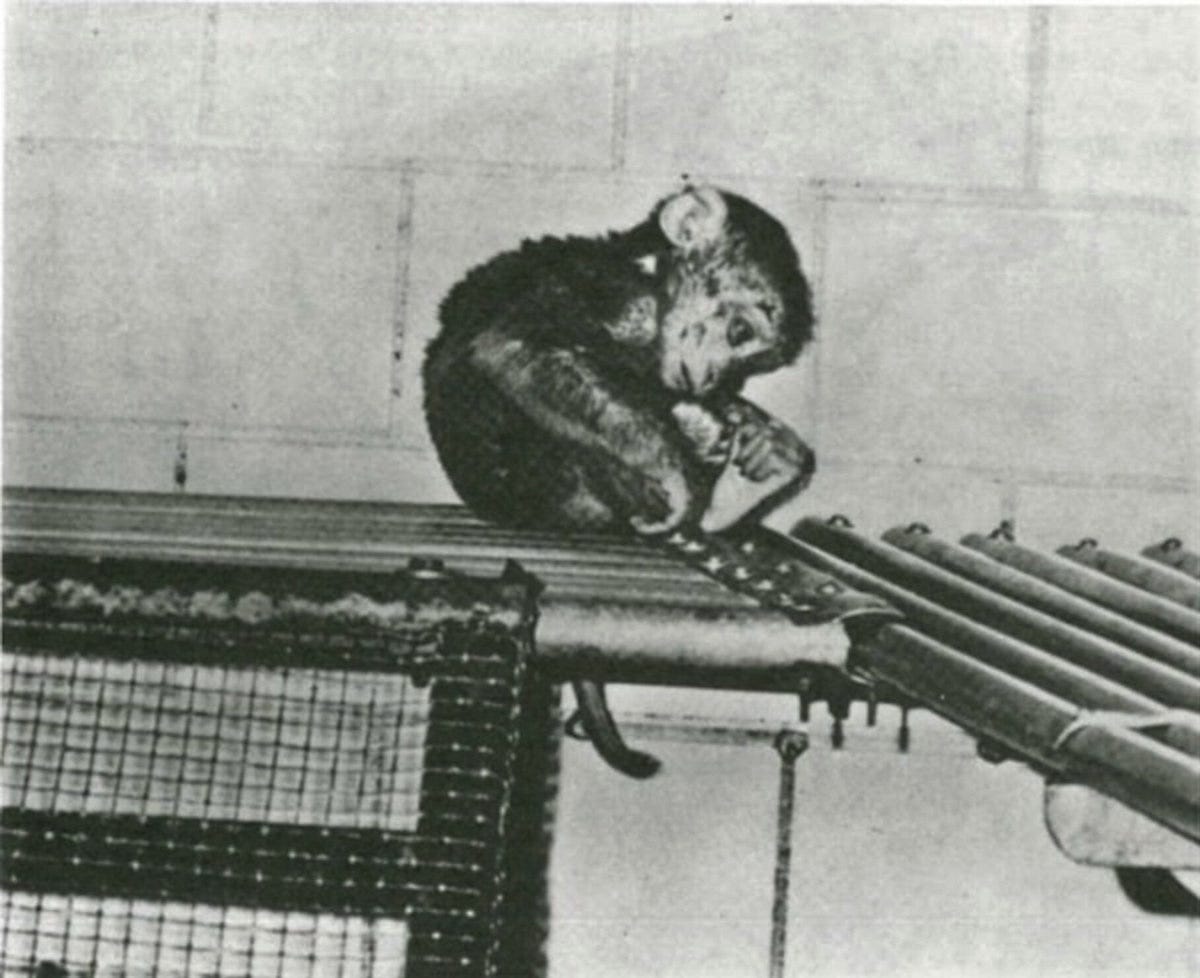

A relevant example from psychology research can be found in Harry Harlow's "pit of despair", do you know of this? So back in the 1970s, young monkeys, rhesus macaques, were locked up in a metal silo and so they were isolated from the outside world and all contact with humans and other monkeys for many months. The monkeys that were locked up were already socialized and normally adjusted, but when they were kept there for a while, they had persisting problems connecting with others - the ability to relate was permanently damaged, and in some cases this had extreme consequences such as the mother monkeys abusing or even eating their own children and other horrific things.

So in various ways abnormal and deficient living conditions can be traumatic in themselves.

Yeah, so what does this have to do with modern society? Well, it can be said without exaggeration that the rise of modern society brought about, to say the least, abnormal living conditions for the vast majority of us.

Karolyn Steffens, in the article "Modernity as the cultural crucible of trauma", writes the following:

"Trauma is responsive to, and constitutive of, modernity". Trauma is a consequence of modernity, at the same time that trauma also builds up modern society, i.e. the idea is that modernity is constructed and recreates itself through our collective response to an ongoing trauma.

Trauma in this sense, she argues, is something uniquely modern that brings about a kind of structural and ideological shift from bodily injury to psychological mutilation and dismemberment, and she sees the root of this in the complex historical process that was marked by profound and extensive social shifts, mass industrialization, urbanization and the tearing apart of traditional societies and family ties. But also in the new political relations, the emergence of the nation-state, in the imprint of imperialism and capitalism on how we understand ourselves and our world around us, and not least technology in all its forms and variants, these tools which in different ways end up between man and his world around us, and creates a distance even though they make many things in our lives easier.

The analysis of technology, vis a vis aesthetics and culture is, perhaps surprisingly, the key to understanding global madness. Kittler notes that the typewriter replaced the flow and sensual movement of cursive writing with a staccato jerkiness, one replete with empty spaces between the letters. By the time of audio recording and then film, the caesura in our reasonings had been incorporated into the production of meaning (like Kafka’s tigers at the temple).

More though, there is a long anticipation of this violence, of industrialized killing. Traverso is right that it began, in earnest with WW1, but the age of mechanical discovery was driven by the logic of a violence and death wish that has reached completion, or nearly, today. Jonathan Beller and Kittler both are rather amazingly close in their reading here.

“The history of the movie camera thus coincides with the history of automatic weapons. The transport of pictures only repeats the transport of bullets. In order to focus on and fix objects moving through space, such as people, there are two procedures: to shoot and to film. In the principle of cinema resides mechanized death as it was invented in the nineteenth century: the death no longer of one’s immediate opponent but of serial nonhumans. Colt’s revolver aimed at hordes of Indians, Gatling’s or Maxim’s machine-gun (at least that is what they had originally been designed to do) at aboriginal peoples.”

(Friedrich Kittler)(John Steppling, “The motorcade drives on”.

In connection with the above, John Zerzan, the American primitivist thinker, writes the following:

Since the Neolithic, there has been a steadily increasing dependence on technology, civilization's material culture. As Horkheimer and Adorno pointed out, the history of civilization is the history of renunciation. One gets less than one puts in. This is the fraud of technoculture, and the hidden core of domestication: the growing impoverishment - of self, society, and Earth. Meanwhile, modern subjects hope that somehow the promise of yet more modernity will heal the wounds that afflict them.

A defining feature of the present world is built-in disaster, now announcing itself on a daily basis. But the crisis facing the biosphere is arguably less noticeable and compelling, in the First World at least, than everyday alienation, despair, and entrapment in a routinized, meaningless control grid.

Influence over even the smallest event or circumstance drains steadily away, as global systems of production and exchange destroy local particularity, distinctiveness, and custom. Gone is an earlier pre-eminence of place, increasingly replaced by what Pico Ayer calls "airport culture" — rootless, urban, and homogenized.

The interesting thing is that these authors' assessment of the state of affairs is neither unique nor particularly new, but reflects the diagnosis that modern philosophy has always, albeit in slightly different ways, placed on its own society.

Descartes' entire philosophy is, in a sense, one big coping project relating to man's existential vulnerability in a time where all traditional relationships are seriously beginning to get torn apart, when the great upheavals of modernity are taking a more concrete form - even if Descartes' thinking still confirmed reproduced this disintegration in his radical distinction between body and soul. And this obstacle that Descartes formulated and then tried to get around is thus, in various ways, taken for granted as a starting point for basically the entire philosophical and scientific work of the modern period that follows.

Hegel, he also clearly sees this civilizational trauma and tries to come to terms with the dichotomies, but then also takes the disintegration for granted. He tries to put the body, the world and the soul back together with the help of his dialectical method. And on this road it is. Immanuel Kant tries to find his way back to the thing in itself, to the unadulterated reality. Durkheim builds the science of sociology around the analysis of anomie and perceived rootlessness. Freud emphasizes how civilization is characterized by a radical "discontent with culture". We have Kierkegaard weaving his philosophy around the concept of anxiety. Sartre's existential desperation and disgust at the experience of being. And Marx, not least Marx, who builds most of his political and economic theory around alienation, around the condition of being alienated from oneself, one's surroundings, and the fruits of one's work.

But the question is whether it really is something that needs to be fixed, or whether all of this is rather a shift in perspective that has most of its explanation on the ethical level, in generations of unhealed and festering wounds.

The question is whether it is not rather the case that we are a bit like those dwarves at the end of C.S. Lewis's Narnia story, the guys who think they’re drinking muddy water and eating pigs' food, although in fact they are in a sort of anteroom to the kingdom of heaven. That the unadulterated whole was actually there all along.

Wittgenstein also says about this – philosophy cannot discover anything new, it can only reveal what has always been there.

+++

Ok, we have some kind of diagnosis, then. Modernity is characterized by separation, and reproduces this separation in our experience of reality and ourselves.

But what does the alternative look like? How can we begin to imagine a life characterized by this which I was talking about earlier, by the "fundamental fact" that precedes the Cartesian cut, a more grounded human existence that precedes this artificial, secondary, and traumatic separation between self and world— between ourselves and our fellow man?

One way to get a little closer to this is to ask two questions – what is the opposite of isolation, and how do people seem to have lived in the hundreds of thousands of years that preceded settled and complex societies?

A central aspect of this is physical touch .

"Are we in the midst of a touch crisis?" asked Claudia Hammond for the BBC a couple of years ago. 2020. During this year, several others are on the same theme, not least of course given the extensive lockdowns and the so-called social distancing that was more or less institutionalized throughout the Western world.

But "We were touch-starved long before COVID-19", however, writes one Roxanna Azimy, and this observation she makes becomes evident when comparing our culture to the condition of human groups living in ways more reminiscent of our distant ancestors :

Barry Hewlett points out in his article "Social Learning and Innovation in Hunter-Gatherers" how "physical proximity and emotional proximity are particularly important to hunter-gatherers (Hewlett et al. 2011):

Foragers prefer to be physically close to others. The compact camp composition described above is just one example of this. When hunter-gatherers sit down in the camp, they are usually touching somebody. Cross-cultural studies show that forager caregivers are more likely than caregivers in other modes of production to hold infants, show more signs of affection with infants, and are more responsive to fussing and crying.

And a particularly interesting example we find in the article "How to Sleep Like a Hunter-Gatherer" written by Jeff Warren from an interview with the anthropologist Carol Worthman who describes how hunter-gatherers sleep, and then she compares their behavioral patterns around sleep with what we can see in the modern western world. The image she then gives is of a social, relational and tactile activity where piles of animals and people from all generations generally sleep together in a sensory-rich environment characterized by touch and community...

“… everyone embedded in one big, dynamic, “ sensory rich environment.” This kind of environment is important, said Worthman , because "it provides you with subliminal cues about what is going on, that you are not alone, that you are safe in the social world ."

So you basically don't lie alone in a bed locked in a room and worry about a thousand different ways in which the world can end at any moment.

…

Worthman continues his reflections by emphasizing how strange and deviant our modern approach to sleep actually appears in relation to the historical norm:

Western sleep, said Worthman, is arid and controlled, with a heavy emphasis on individualism and the “decontextualized person.” Contact is kept to a minimum. “I mean, think about it—this thing, this bed, is really a gigantic sleep machine. You've got a steel frame that comes up from the floor, a bottom mattress that looks totally machinelike, then all these heavily padded surfaces—blankets and pillows and sheets.”

It's true. Most of us sleep alone in the dark, floating three feet off the ground but also buried under five layers of bedding. I had the sudden image of an armada of solitary humanoids in their big puffy spaceships drifting slowly through the silent and airless immensity of space. "Whoa," I said.

Worthman nodded. “I know, I know, so weird.”

+++

And all of this says more than you might think. Because in sleep, there is a kind of regression to the inner depths of the beings we are - and in this state, in the vulnerability of sleep and naked contact with our innermost being, we modern people are alone, framed by a kind of concrete machine metaphors. But among hunter-gatherers, sleep is instead about a social and relational activity characterized by touch and organic community.

These are two radically different realities. Deeply different ways of being.

And something that philosophy has acknowledged more and more in recent decades, especially within the framework of phenomenology, is how physical touch, and the relational, emotional, and cognitive resonance that goes with it, has a central existential significance.

It thus plays an important role in the ways that are available to us to exist as human beings – touch is decisive for the forms of experience and modes of perception that become available to us, but also for our very nature as experiencing beings.

In Cartesian modernity, it is a reasonable question to ask if other people are actually conscious, and a common position is also that it is something we can never be completely sure of. But e.g. among the San people of southern Africa, where immediate relational existence as relational beings embedded in the world entirely precedes this abstraction of the separate individual, that question is not even possible to formulate. It is an existential fact that we are connected with other conscious beings.

Yet we had to put little monkeys in a fucking metal silo for nine months to figure out that this would actually hurt them.

This emptying of meaning from nearly all of daily life may be the most significant experience of the 21st century. The emptying takes several forms, though, I think. Beller is right that there is a psychotic coercive quality to much of the ‘data’ or information one is given.

The transference of labor to the consumer means endless amounts of time spent navigating the (intentionally, i think) badly designed web pages or automated phone answering systems. And there is simply the almost offhanded coercion of all marketing. And nearly all of life is marketing now. Politics is marketed, certainly. War is marketing for those not directly involved in the war. War is sold. War is purchased, passively or actively. But the point is that life is diminished through this inexorable emptying. And the perhaps surprising Walter Benjamin quote at the top of the page enters our discussion at this point. Adorno said arguing aesthetics is crucial in all things (I paraphrase). He meant arguing in even small matters. That having taste, that evaluating aesthetically was a matter of importance. It was moral.

(John Steppling, ibid.)

Kym McLaren at Ryerson University in Canada emphasizes in her article "Touching Matters" how touch partly grounds our conscious, embodied existence, but also how it can enable this kind of relational being, i.e. a form of subjective human condition that is immediately united with other thinking and feeling persons. So it is not a question of a philosophical interpretation tool to secondarily organize and categorize sense data or something like that, but of something that goes to the very bottom of what it means to exist. This utterly relational existence seems able to open up to us a completely different kind of subjective intentionality that precedes rational reflection, a kind of ground state that is actually radically different from our modern and Cartesian experience.

"Here, we find an intimacy that is not simply one of knowing another and/or being known by the other, as if who we each are were already established and we needed only for our minds to understand each other. Here we find an intimacy that consists in becoming oneself through the other. Through others' touch, we grow into ourselves, become more than we were by developing not only a new living affective sense of our own body, but also, more fundamentally, a new organization of that body even (if we return to the example of newborn infants) new ways of breathing and heart beating.

One is born anew through the other's touch.”

Where do I want to go with all this then?

Yeah, so, in this shift in perspective that I am trying to argue for, the contours of a more radical answer to the basic Cartesian problem lie.

And this answer is all the more radical because it not only reflects upon the premises we get from the original formulation of the problem, and sort of tries to find ways around the problem while leaving it intact, which is what e.g. Kant and Hegel did. And it's also not about trying to live with the problem in the same way that Kierkegaard or Nietzsche suggested we should.

This shift in perspective, which emphasizes the possibility of an original and undivided relational existence, rather uproots the whole problem. But part of this way of handling the problem is about... That philosophy alone is not sufficient to solve the problems that philosophy can identify. It may be able to find answers, but somewhere we also have to start putting these answers into practice for them to bear fruit.

And this can actually be connected with one of Wittgenstein's later insights – that philosophy doesn't really create anything new, but only reveals what was actually there from the beginning. And the question then is what to do with what we discover.

In any case – this relational perspective on human being can perfectly well be anchored purely rationally with the help of introspection. That is we can reflect on our immediate experience and conclude that our conscious selves, whatever they consist of, have a fundamentally relational character. Being aware at all, for example, is dependent on us aiming at something. That there is something we can be aware of. There is a kind of ontological reception in our subjective experience that is absolutely indispensable for us to exist at all.

After all, Descartes' famous motto is about I think, and the conclusion is that I therefore exist. But it is just as obvious to say that I THINK, and then conclude that what I THINK exists. This also applies when we reflect on our own self as an object. We must aim at something, even if it is only a fantasy or an abstract idea, in order for us to be conscious beings. We must have something to know together with.

Root: con-scire.

To know together.

(It can also be said that AS SOON AS WE HAVE MADE THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN THE SELF AND AWARENESS, THEN IT FOLLOWS THAT THE STATE OF THE SELF IS DEPENDENT ON THE CONTENT (I experience X) THAT IS EXPERIENCED FOR THE AWARENESS TO BE ABLE TO TAKE PLACE AT ALL IN THE SUBJECT/SELF.)

In any case - both pieces are needed to actually describe the reality that appears to us within the framework of our immediate experience. The subject and the object are dependent on each other, they are parts of the same spectrum, rather than absolute opposites, and my position here is that the subject can therefore only exist as precisely a subject through a relational reception of a surrounding world, and it then follows that the conscious observer is not actually conceivable as an abstract and cut-off Cartesian substance. There exists nothing like that in reality.

And it is from this point of departure that we can begin to talk about the composite subjects and the common perception that the somewhat misleading title of this lecture introduces.

And if we're going to tackle compound THINGS and their metaphysics, there's no one better to go to than Thomas Aquinas. Without digging too deeply into his thinking, we can state with him that if the subject is a relational phenomenon, it is also something composite. And something that is inherently composite, regardless of whether we understand it as a substance or a process - it is dependent on its parts. That is the composite object or subject derives its character from the various constituents with which it is in harmony and is built up from. It does not derive its character from an absolutely simple and independent nature or essence, and it is in this latter way that we often think of consciousness after Descartes.

The consequence is that our perception itself must be regarded as a composite object that is constituted relationally in relation to the outside world. And this is a more radical claim from our modern conception of reality than one might think at first glance, because it implies that awareness takes place TOGETHER with other really existing things. That is, I do not see the tree outside my window in an object-subject relation where I am external to an object that is passively viewed. It is rather that the tree together with me constitutes a subjective experience as a relational phenomenon - and the remarkable consequence of this shift in perspective is that what we call consciousness, at its most basic level, is something that you and I do together, completely in line with Immanuel Levinas’ observation that that which is myself first comes into being in the encounter with the Other.

But while this is obvious in the case of such objects as are directly accessible to our senses, such as the tree outside our windows, how can we say with certainty that this relational subjectivity engages other persons , i.e. other conscious beings?

Well - we can be directly aware of other beings' intentionality - their active wills, intentions, and how they direct their perception. It is enough that you touch me in a way that expresses your presence or conscious intention, or that you say something to me that expresses an propositional or an emotional mood or whatever - and that this which you do to me or say to me is something towards which my awareness must be directed.

So the point is that I must be receptive, that I must be receptive in relation to your expressed intentions in order for to be aware of them as actual or potential intentions at all. And when your intentions emerge before my awareness like a symphony I have never heard before or a novel I have never read before – ie. when I step by step have to discover your intentions precisely as something I did not have in my consciousness before they appeared to me, and which I also cannot understand until I see the totality of what you express - then it is an immediate fact that what emerges is not something I actively project onto the outside world that was already with me beforehand. Your intentions are something I detect. From whatever they originate, it is not my active will or conscious activity that produces them.

And since this also regard intentions, idea content, intentions, emotional resonance or the like - it is also about something that by definition originates from another conscious being.

Our composite selves absolutely have what we might call a Cartesian "self-part" of immediate awareness that is ours and no one else's. But it can only be realized relationally. And when we go beyond logs and trees and stones, and take in this tangible intentionality of other subjects as a possible part of the composite object that is ourselves, it immediately follows that the very basis of our subjective perception, this Cartesian self-part, can potentially be realized by and in relation to other subjects. Other self can thus be an immediate constituent of your self as a composite subject.

That is you can experience the world in and through other external subjects. A state of consciousness based on the interweaving of one's own self's intentionality with other subjects thus becomes a clear and distinct possibility.

It is precisely this that Martin Buber emphasizes when he talks about the fundamental experience of the fellow man before us:

There is no I taken in itself, but only the I of the primary word I-Thou and the I of the primary word I-It.

If I face a human being as my Thou, and say the primary word I-Thou to him, he is not a thing among things, and does not consist of things.

The Fuegian ( he talking about the South American ones the indigenous peoples down on Eldslandet ), The Fuegian soars above our analytic wisdom with a seven-syllabled word whose precise meaning is, "They stare at one another, each waiting for the other to volunteer to do what both wish, but are not able to do." In this total situation the persons, as expressed both in nouns and pronouns, are embedded, still only in relief and without finished independence. The chief concern is not with these products of analysis and reflection but with the true original unity, the lived relationship.

(The mystery of the minutia that holds together the components of the subjective self? But that minutia, that haecceity is itself contentless and can be combined and realized together with basically any composition! AND THAT'S JUST ONE INGREDIENT)

The true original unity. The lived relationship.

And so this is where I wanted to go with all of this. That there are concrete solutions to this basic problem that characterizes the entire modern history of philosophy. That we can even pull it up by the roots and throw it on the fire.

But the traumatic existential experience that gives rise to the problem tends to remain untouched. And when it returns into view, the basic problem must once again be “philosophized away”. Time and time and time again.

Pierre Hadot believes that classical philosophy primarily had a therapeutic function. It can help us find our way in an unbearable reality by changing our value judgments. It's true. But I don't think we should settle for that. If all philosophy helps us to do is find our way around a fundamentally unsustainable situation, then it is nothing more than the opium of the people that Marx criticized.

Because if it is true that we are actually dealing with an ongoing traumatic process that lies behind this recurring problematic existential experience that we can then only temporarily solve or process with the help of philosophy - then philosophy is not enough. Then we may have to use other tools to get to grips with the situation behind all of this. Ethical tools, political, aesthetic, religious. There are many options.

What philosophy can do, just as Wittgenstein says, is to help us become aware of the possibilities that were there all along. It can reveal the world around us and show what it really looks like, and it can ask questions. Fashion a diagnosis for society's various basic problems and help us understand where the fault lies and what could be done.

But when push comes to shove, sometimes we have to put the theories aside and actually act. Thus, it’s not enough to just reflect on life.

Sometimes we have to try to live it too.

Fuck off

Get free

We pour

light on

e v e r y

t h i n g

And this I learned and thus I gleaned

What we loved was not enough

And the days come when we no longer feel

There'll be war in our cities

There'll be riots at the mall

There'll be blood on our doorsteps

And panics at the ball

All our cities gonna burn

All our bridges gonna snap

All our pennies gonna rot

Lightning roll across our tracks

All our children gonna die

So good night vain children

Tonight is yours

The lights are yours

If you'd just ask for more

Than poverty and war

If you'd just ask for more

What we loved was not enough

But kiss it quick and rise again

Thank you for your post. "Loo-ceee! You got some 'splain' to do!" Philosophy. Psychology. Religion.

I agree. The best we can think of serves to shed light on what is already there. Of course, the quality and spectrum of the aforementioned light that is shed and the reliability of the eyesight of the viewer of what is revealed all factor in what is declared as "there". The declaration is unreliable.

I do get annoyed with people romanticizing ancient cultural situational ordering of "how it was in the good ol' dayz". I mean, people in the "hunter-gatherers" collectives slept in large lumps not because touch was a vital component of well-being and they understood it as such, but for survival. Warmth. Protection. Infants were quieted more so than today so as not to draw attention from predators.

Can any of us actually imagine sleeping in large and stinking piles with other people farting and snoring and thrashing and screwing each other and lice and fleas, etc., etc.? I always laugh when I read this kind of nonsense as if primitive tribes had it all figured out knowing the authors of such nonsense would likely run screaming from the cave in the very traumatized condition they claim sleeping in large touchy-feely groups prevented. Why does anyone assume that kind of communal sleeping arrangement leads to a "good" night's sleep? No thank you. I like the luxury of sleeping alone on a bed. I also understand others like sleeping with others. One is not necessarily superior to the other.

That's my primary problem with most philosophies or psychologies. They seek to not only shed light on what "is", but then strive to cure it or explain it all away. In my experience, life is so much larger than that and the very moment we strive to control it is interestingly the same moment we lose any illusion of control over it because the truth is, as far as I can see, we have no control over it. This truth I have witnessed confirmed continually.

The best we can hope for is some degree of control over ourselves, but even that is partially illusion as is illustrated time and again that when confronted with various circumstances we surprise ourselves with our response despite all best efforts at control of oneself.

This construct of a "world" whether it be today or thousands of years ago is a pack of lies. Piled on top of one another like a haystack. The more we insist we will ferret through the hay and find that needle of truth, the more ridiculous it becomes because there is no needle of truth to be found in a stack of lies. Only more and more lies.

As the lovely song you linked says, what we loved was not enough. We don't love God. He's too large for most of us to love or to contain within the pages of any book or man made construct we call "religion" that we can delude ourselves with. We want a "small" love that feels "safe", so we trade the terrifying enormity of loving God for the disappointing barter of loving one another, at best. Or ourselves. Or nothing at all at worst.

Let the malignant psychos play out their best game at trying to control everything. They have lost before they even began. Though I have no doubt as they play out this losing game it will be painful for everyone. I say, so what? Regardless. And damn the torpedoes.

I sincerely hope people will leave animals alone and stop lying to themselves that whatever response an animal has to a circumstance or a substance somehow reflects how it affects people. It is evident we are not the same. It's cruel to keep insisting we are. All the way around.

Very well written. I really appreciate how you merged philosophy and psychology. My background is in psychology and there is a quality to trauma that solipsism emerges as a protective mechanism.

Like you said, experiencing trauma can lead an individual to turn their focus inward, towards their own personal and subjective experiences, as a way to shield themselves from potential harm. This internalization of their thoughts and emotions creates a separation and isolation from the external world, paralleling the philosophical concept of solipsism, which questions the existence of reality outside of oneself. Consequently, the impact of trauma in the modern era is intricately entwined with philosophical musings, as it shapes and influences our understanding of the world.

But it always comes back to the *I*, because the root of trauma is that the I is threatened and needs to be protected. The traumatized sense of self remains pivotal in this scenario, as trauma inherently disrupts and jeopardizes the wholeness of an individual's subjective perception, serving as the main locus of both the traumatic event and its subsequent reactions. This astute observation sheds light on the inherent constraints within the presented perspective.

Here's a related back-and-fourth with radical solipsism. Somebody tells me "how do you know you exist?" and I respond that if they really believed I didn't exist they wouldn't be talking to me because I would have to have existed to ponder the question to being with. It's like writing me a letter telling me the mail system doesn't work, or calling me to tell me the phone doesn't work.

Just as your article argues solipsism relies on but denies the prior fact of the self's connection to the world, so too this philosophical question assumes the existence it aims to undermine. Both trauma and philosophical stances like solipsism rely on a more basic intertwining of self and world for their very possibility, even as they propose a notion of separation. This reflects how experiences of harm and threat arise and are addressed within fundamental social and environmental bonds. This radical stance, meant to protect the *I*, by denying the reality of the world and others outside the self, could exacerbate and prolong the traumatic effects.

By situating itself solely within the private subjective experience of the "I", radical solipsism fails to adequately address or resolve the psychological effects of trauma. By restricting itself solely to private subjective experience, radical solipsism remains trapped within trauma's isolating effects and does not provide a means of reconstructing the relational and external dimensions necessary to psychologically resolve and recover from the traumatic experience.

Another thing I learned from psychology is that "problems created in isolation cannot be resolved in isolation." Psychology indicates that fully addressing issues arising from isolation or external harm requires moving beyond a solely isolated perspective to rebuild connections severed and re-engage factors involved in their creation.